If you recall from volume two, the five Pandava brothers and their shared wife Droupadi began their twelve year banishment to the forest. Volume three takes us up to the end of that exile. After year twelve, in volume four, they must go to a city and live for one year without anyone recognizing them. If they do that, according to the terms agreed to back in volume one, they may then return to their empire and repossess it. In their absence, Duryodhana has enjoyed playing at emperor, and of course we know he will never relinquish his power after having gotten used to it. When we get to volume five, a big battle will take place, and the Pandavas will win. We know all this now, but first, they must endure the twelve-plus-one-year exile.

They spend most of the forest years going from one sacred place to another and performing the rituals appropriate for each holy place. Every place they visit has a story about what makes it noteworthy. In the first few pages of this volume, an adviser gives the Pandavas a rundown of all the sacred places they ought to visit. Reading those chapters felt like listening to an excited friend telling me about all the places I simply must see on my upcoming trip, and every restaurant I must eat at.

After the overview, the Pandavas travel all over India racking up spiritual points by honoring each station. The stories vary widely in how much disbelief we must suspend, make the reading both unpredictable and entertaining. I really like how the narrator just throws in something totally outrageous now and then without explanation. At one point, for instance, we learn that a fellow had two wives. One bore him a single son and the other bore him 60,000 sons. We get not a hint about how she managed that trick. But later in the story the father needs a big hole dug pretty quickly in the dried ocean bed, so he gets his sons to do it for him. This function in the story called for a lot of people; 60,000 sons must have seemed about right.

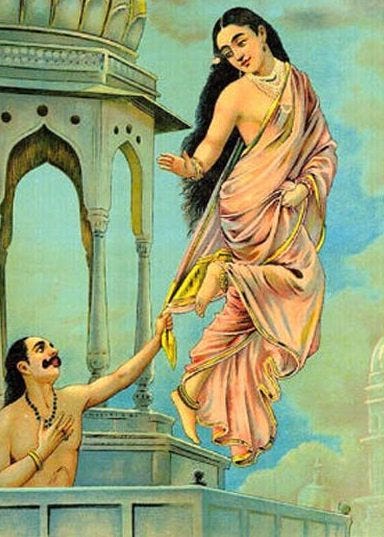

Some of the stories get pretty funny, too. During a severe drought in one kingdom things become desperate. It seems that only one man, Rishyashringa, has stored up enough austerities (sort of like spiritual vouchers) to save the day. Unfortunately, he lives with his father in a hermitage, and the king of the drought-stricken region can’t get him to come use his austerities and save them. The son has been raised by his dad in isolation, and has never seen a woman, so the king gets an older courtesan to come up with a plan. She builds a floating hermitage that she moors nearby and sends one of her girls on sort of a Mata Hari mission to pay a little visit to Mr. Innocent. When dad is away, the young courtesan brings some delicious ripe fruits and introduces herself to Rishyashringa, and the two engage in innocent chitchat. Then she starts getting playful and a bit physical with the confused young man.

Then, as without shame, and overcome with liquor, she tempted the maharshi’s son. Having seen the change in Rishyashringa, she pressed him again and again with her body. Then, pretending that the time for agnihotra had come,1 she slowly went away, casting backward glances. At her departure, Rishyashringa was overcome with desire and lost his senses. Because of his feelings for her, he felt great emptiness. He sighed again and again in distress.

Well, daddy comes home and sees right away that something has happened, since sonny boy has neglected all his chores. He asked if anyone had visited the hermitage while he was out. Rishyashringa says that a wise man of unusual appearance had visited, and offers a detailed description, which I’ll give in part.

“His eyes were beautiful and black and white, like those of chakora birds. His matted hair was blue, clear, fragrant and extremely long, and braided with golden thread. Like lightning blazing in the sky, there were two receptacles under his throat. There were two balls under his throat. They had no hair on them and were extremely beautiful. His waist was thin around the navel. But his hips were expansive.”

Despite the faulty pronouns, dad figures out pretty quickly what has gone on, and he tells his son that a demon had visited him, and he mustn’t have anything to do with it again. Soon enough, though, she shows up again while dad is gone. “As soon as he saw her, Rishyashringa was delighted. His mind was deluded and he told her, ‘Let us go to your hermitage before my father returns.’” So she gets him into the floating hermitage and sails back to the drought-stricken kingdom.

Everything turns out well, by the way. In fact, a lot of these stories end with everyone breaking out musical instruments and throwing a big party.

Roughly the first half of this volume contains such local lore. For the second half, we travel with the Pandavas and learn about their own adventures. At one point Droupadi gets abducted and rescued. But in the middle of that adventure, we hear another story about a similar abduction and rescue. In fact, on several occasions, the Pandavas get encouragement from well-wishers by hearing stories about others who went through similar tribulations. Of course this entire epic must have served that same function for its many audiences through the centuries.

Mixed in with all the storytelling, we frequently get little sermons about virtue, propriety, and morality. For instance, in chapter 493, Yudhishthira asks about the supreme greatness of women. We then get a litany of women’s virtues, which comes across, not so much as a laudatory description of females but as a training manual for women on how to serve their men—but also as a catalogue of what level of devotion husbands should demand from their wives. After this chapter, several stories center around faithful and devoted wives.

One such story struck me as particularly touching. Savriti, referred to as “the large-eyed one” and “the unblemished one,” chose Satyavan for her husband, despite the fact that a sage told her he would die in a year. Satyavan knew nothing of his coming death, and Savriti did not tell him. On the day she calculated he would die, he went into the forest to collect wood and she insisted on going with him.

She seemed to be laughing, but her heart was miserable. The large-eyed one saw colorful and beautiful woods in every direction, resounding with the cries of peacocks. Satyavan spoke these sweet words to Savriti. “Behold the rivers full of sacred waters and these supreme trees in blossom.” The unblemished one always watched over her husband. Remembering the words of the sage, she thought that he was already dead. Walking gently, she followed her husband. Her heart was cleft in two and she waited for the time.

This juxtaposition of the beauty of the natural world and Savriti’s awareness of approaching doom—an awareness she keeps to herself—seemed very modern to me. It reminded me of Robert Jordan’s sharp awareness of the new spring growth while on a suicidal mission in For Whom the Bell Tolls.

Besides stories about individuals, and the various morals one should draw from those stories, this volume includes some much grander narratives, about the cycle of lives through reincarnation, the four ages of a universe in decline, and even lectures on values, sense perception, and epistemology. We gradually learn about the Hindu ontology—the various beings who populate the universe: gods, rakshasas, various demons, and so forth. The epic largely presupposed its audience already knows the myths about the thirty gods, but it sometimes expands on that knowledge.

So far, the most striking feature of the Mahābhārata lies in its thoroughgoing optimism. It acknolwedges the presence of bad people, evil intentions, natural disasters, curses, and unavoidable fates. But all of these stories offer a comforting sense of a rule-bound, ultimately just world—appearances to the contrary. Yudhishthira occasionally sits down and despairs, but he receives consolation from pulling back and looking at the bigger picture. His exile has not ended his life, and his death will not end his story. Suffering means purification; evil comes from emotions running amock, but we can control them; failures in this life merely serve as placement tests for the next life; and when the universe has reached the nadir of its decline in the Kali Yuga, it, too, will reset. Eventually everyone achieves salvation, some later than others. To me, this epic reads like Groundhog Day for all humanity.

I’ve learned quite a bit about Hinduism from these works and also from the non-fiction book I’m reading in lieu of a biography, The Hindus: An Alternative History. In the latter book, though, I still have another thousand years of history to go before reaching the time of the Mahābhārata’s composition. Stay tuned for updates. And do check out Naomi Kanakia’s substack, Women of Letters for her thoughts on the Mahābhārata and on growing up Hindu in the United States.

§ § §

I have recently started to question approaches to literature that involve interpretation, or trying to uncover a (or the) meaning of a work. Instead, I have begun looking at approaches that focus on the fictional experience that emerges within the reader while performing the act of reading. So, in my copious spare time, I’ve started looking at some of the writings of proponents of reader-response criticism. Next week, therefore, I plan to reflect on the experience of reading Mrs. Dalloway, by Virginia Woolf, since Woolf employs a stream-of-consciousness narrative in it.

Thank you for reading my thoughts on these great works of literature. I appreciate your support and comments. If you haven’t subscribed yet, please do, so you’ll receive each reflection by email as it comes out. Also, if you want to send some money my way, consider upping your free subscription to a paid one. I won’t stop you. But I get great satisfaction simply from knowing that you give me your time and energy to read these thoughts.

Works mentioned in this reflection

The Mahābhārata, translated by Bibek Debroy

The Hindus: An Alternate History, by Wendy Doniger

For Whom the Bell Tolls, by Ernest Hemingway

Mrs. Dalloway, by Virginia Woolf

Groundhog Day (1993), directed by Harold Ramis

A sacred fire ritual.

An interesting read. I was raised Hindu (and have read the Mahabharata. My interest in reading your piece was to learn a bit about how the story reads to a Westerner, without context of the culture and religion. My take-away from Hinduism and from the Mahabharata isn't that it hypothesizes that the world is just or rule-bound - though, Hindus call the religion "Sanatan dharma", which roughly translates to something like "the eternal law" or "the eternal path" - a set of rules and guidelines for living life, so to someone more familiar with the Abrahamic traditions Hinduism would probably appear quite rule-bound. The Mahabharata is a later epic, when the world was less rule-bound and more sinful or just than the Vedic era (etc), for example - it is set during the third of four eras. A bit more context: the story of Savitri and Satyavan is a famous one - most children already know it and it's frequently told.

You are definitely The Man, RBS.