Before last week, I had virtually no knowledge of Hinduism, so I will have to learn as I go; and I plan to read The Hindus: An Alternate History, by Wendy Doniger, in lieu of a biography.

It all began over such a little thing. One day King Parikshit, normally a great guy, had gotten tired and thirsty and apparently a tad irritable during a hunting trip when he stumbled upon a hermitage where a sage sat meditating. The king asked for water, but the sage, deep in meditation, didn’t notice him. So King Parikshit took offense. He saw a dead snake on the ground, and, picking it up with his bow, draped it over the sage’s neck. That’ll show him, the king must have thought. The sage’s son, himself also a sage, found out about the snake prank and got a lot more upset than you would expect a sage to get. He cursed King Parikshit saying he would die from a snake bite within a week. When the dad woke up and heard what his son had done, he sent warning to the king. A snake, actually not just any snake but Takshaka, the king of snakes, managed to get at Parakshit despite all his precautions. That trick makes for an interesting story by itself, but, long story short, Takshaka bites and kills Parikshit.

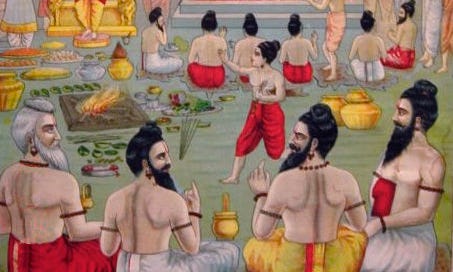

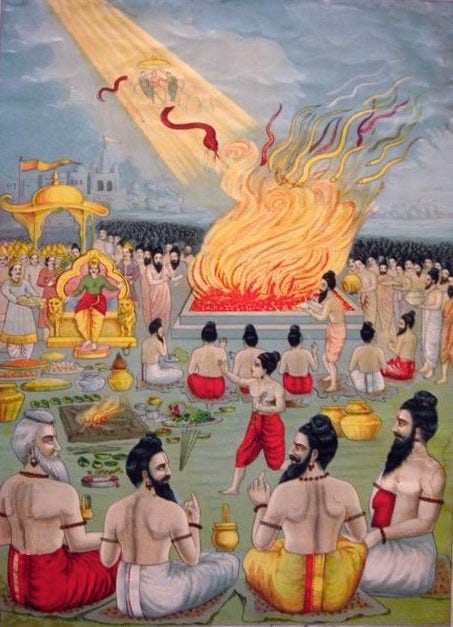

The king’s son, Janamejaya, then organizes a huge snake-sacrifice, to avenge his dad and destroy all the snakes of the world, poisonous or not.

The snake-sacrifice then started according to the prescribed norms. The officiating priests, who were learned in their respective duties, went about prescribed tasks. They dressed themselves in black garments and their eyes became red from the smoke. Chanting mantras, they offered oblations into the sacrificial fire. As they poured oblations into the mouth of the fire and uttered the names of the snakes, the hearts of the snakes trembled in fear. Thereafter the snakes dropped into the blazing flames, wretched and screaming piteously at each other. They swelled, breathed hard and intertwined their heads and tails. In large numbers, they fell into the blazing fire—white, black, blue, old and young. Crying out terrible screams, they fell into the lofty and blazing flames, in hundreds, thousands, millions and tens of millions. (Astika Parva, chapter 47).

But then, in the middle of this herpetocidal frenzy, Vaishampayana arrives on the scene and recites to Janamejaya the history of Janamejaya’s family, the Bharatas. Vaishampayana has learned the history by heart from the sage who wrote it, Vyasa. (Considering that the whole story runs to about two and a half million words, that feat of memory puts to shame the Greek rhapsodes who only memorized the Iliad and the Odyssey.) The date of its composition? Sometime between 300 BCE and 300 CE.

Janamejaya’s great grandfather, Arjuna, and his brothers got into a conflict with another branch of the family (the Kauravas) over who should inherit a kingdom. The Mahābhārata tells the whole story of how the conflict got started, how it led up to a great battle, and the aftermath, along with hundreds of smaller stories along the way and many stories within stories. In fact, because the Mahābhārata starts with an account of the snake sacrifice, it actually contains a recitation of itself. Every chapter I’ve read so far either begins with the words, “Vaishampayana said,” or it begins with Janamejaya asking a question, or once in a while it starts with some character telling a story within the larger story.

I found the stories themselves simply amazing. Despite their formulaic narrative, they gripped me and kept me wondering after almost every break, “And what happened next?”

Since the tales deal with humans, gods, and everything in between, it feels like anything could happen. Takshaka, for instance, king of the snakes, snuck past the snake-proof defenses that Parikshit had devised by taking on a human form and pretending to be a wise man.

The births of heroes and their enemies often involve miraculous events. For instance, the Kauravas, the hundred brothers who battle with Arjuna and his brothers, all managed to get themselves born from one mother at about the same time. The mother had shown great devotion to her husband and thus got to ask for one boon. She asked for a hundred sons. Well, she conceived all right, but after two years she just had a big lump in her belly but no sons. She hit herself in frustration and out popped a large, dense mass of flesh. Following the advice of a wise sage, she cut the mass into one hundred and one little pieces and put each piece into a small pot with some ghee. After a while she found baby boys in each of a hundred of the pots and a baby girl in the last one. Voilà! The original test-tube babies and, presumably, the noisiest household you could imagine.

It may seem that in such a world, anything goes, but the events still operate within boundaries. To me, the most surprising limitation entails the impossibility of retracting one’s words. A curse, for instance, even if spoken by mistake or in ignorance or from irritation, takes on a life of its own and becomes an inescapable fate. The curse laid on Parikshit provides one example. Another, more awkward one, comes from the time when Arjuna’s mother learned that Arjuna had won the grand prize at a contest. He and his brothers had agreed to always be equals, so mom, thinking Arjuna had won a bag of money, absentmindedly told him to share his prize with his brothers. Turns out he had won a wife. Let’s just say that some interesting stories resulted from everyone trying to make good on that command. One man having five wives wouldn’t have raised any eyebrows, but one wife having five husbands? How the heck? Since that little problem has downstream consequences I’ll talk more about it in a reflection on a later volume.

A couple of other things jumped out at me besides the irreversbility of words. Over and over again, when someone asks a question or seeks advice, the narrator tells us that so-and-so thought for a while and then answered. Now, that doesn’t seem like a big deal, but after dozens of times, it starts to contrast dramatically with the times when someone acts impulsively and eventually comes to regret it. Controlling one’s anger, avarice, lust, and so forth soon emerges as a major theme. And although some things (like the consequences of a curse) may seem fated, the constant reminder of deliberation as an option suggests that thoughtful self-control may play a large role in our lives. I don’t see a lot of that in early Western literature. Most of the great heroes of Greek legend acted out of passion or pride. Even when Odysseus thinks, he mostly schemes. Many of the major and minor figures in the Mahābhārata, on the other hand, when the arrows of the love god haven’t driven them insane, seek a balance between conflicting duties or look for a way to thread a needle between conflicting constraints.

Another pattern that jumps out at me has to do with the way people greet each other. Over and over again we see descriptions indicating that the main conversation doesn’t start until the visitor has “finished all actions in accordance with the proper rites and had prayed to the gods and offered water to the ancestors.” Maybe not in those exact words, but clearly some preliminary rituals or niceties commonly take place, in which both parties display respect for each other. Sometimes in the throes of love, the praises become absurd.

The ruler of men then addressed the black-eyed one in these words, his heart burning with the fire of desire and his words weak with emotion, “O black-eyed lady! O fortunate one! I am burning with desire. O lady with the large eyes! I am seeking you. Accept me in return, because my life is ebbing away because of you. O you whose complexion is like the inside of a lotus! Love’s sharp arrows never stop piercing me. O fortunate one! The god of love has bitten me like a large snake. O one with the unblemished face! O one with the tapering thighs!”

It goes on and on. Her answer, by the way, amounts to, “Talk to my dad.”

This entire work consists of eighteen parvas, or books. The first one, the Adi Parva, gets things going by giving the story of the great snake-sacrifice at which Vaishampayana relates the epic of the huge battle between the two branches of the Bharata family that I gather will take up much of the Mahābhārata. This first volume gives some introductory stories, sets up the story-within-a-story framework, and then tells how the conflict got started. The edition I’m using, beautifully translated with extremely valuable footnotes by Bibek Debroy, consists of ten volumes, so I will post some reflections after each volume in between other books of the Decade Project.

§ § §

Next week, I expect to return to Russian literature and examine Anton Chekhov’s comic play, The Seagull, translated by Marina Brodskaya.

Books mentioned in this post

The Mahābhārata, vol. 1, tr, by Bibek Debroy

Thank you for reading my reflections on great works of literature. If you haven’t already subscribed, please consider doing so, either at the free level or the paid level. Subscriptions at any level boost my ego and keep me on track. Your comments also keep me honest.

> He cursed King Parikshit saying he would die from a snake bite within a week.

Wicked. Imagine going through a week knowing death is certain from a snake bite, no sleep, not a moment' peace, seeing visions of snakes everywhere you look.

Love the babies in pots! Are you sure this isn't another script for Looney Tunes? :)