In The Cherry Orchard, as in his previous plays, Chekhov does not give us a protagonist. Instead, he gives us two central characters around whom the main story turns: Ranevskaya, the matriarch of the family, and Lopakhin, a businessman. Many other characters interact with these two, of course: Trofimov, formerly the family tutor, has spent his adult life as a student; Varya, Ranezskaya’s adopted daughter, has managed the estate for years; Pischik, a neighboring landowner has incurred debts and needs a loan. These and about ten other characters have speaking roles. So, although I focus on the relationship between Lopakhin and Ranevskaya, the story contains many moving parts. Chekhov presents all the characters as people with virtues and flaws, so we sympathize with them at some points and criticize them at others. As an audience, we experience a range of feelings about them, but we can’t readily identify with any one character.

In Act One, Ranevskaya and her biological daughter Anya return to the old family estate after living in Paris for five years. The mother’s debts have grown so great that they must auction off the estate with its magnificent cherry orchard. Lopakhin tells her she can keep the property by cutting it into smaller lots and building summer rental cottages, but the orchard would have to go. Ranevskaya rejects this plan as “vulgar.”

Lopakhin points out that many things have changed in the last few decades, creating new investment opportunities. Cherries, he explains, no longer make money. One can do nothing with a magnificent orchard but admire its beauty and reminisce. However, the new middle class likes to travel, making rental cottages a perfect use for the land. He offers to go into the venture with her, but she won’t hear of it. Instead, she pins her hopes on her brother, Gaev, who says he can buy the property at auction with borrowed money.

Forty or fifty years before the play begins, Czar Alexander II had emancipated the serfs. Lopakhin, the son of a land-bound serf of the Ranevskaya estate, has made good financially but still harbors painful memories of his childhood and feels inadequate. The modern age paved the way for unsentimental investors like him and handed new power to former serfs and their descendants. Ranevskaya, however, like a Russian Scarlett O’Hara, clings to a romantic nostalgia for pre-emancipation times. Some household serfs, unlike the land-bound serfs, chose the relative security of serfdom over freedom. In the play, old Fiers, has taken that route and stayed on with the family until he can no longer work.

In Act Three, we learn that Lopakhin has outbid Gaev and bought the property himself at auction. He recounts each step in the bidding with pride, oblivious to the effect his gloating has on those around him. Wasting no time, he begins putting his moneymaking scheme into action.

Act Four picks up two months later as the family, surrounded by suitcases, bags, and piled up furniture, prepares to leave forever. We hear the sound of men chopping down the trees. Someone asks Lopakhin to hold off until the family has left, out of respect for their feelings, and he does so. But the destruction resumes at the end of the act.

Chekhov insisted on calling this play a comedy (“The Cherry Orchard: A Comedy in Four Acts”). While he does include several comic scenes, he also forces the audience to confront the ongoing upheaval of Russia as it transitions to a market economy. In Lopakhin, he captures the pent-up resentment and energy of the new merchant class; in Ranevskaya, the nostalgia of a vanishing nobility; and in the perpetual student, Trofimov, the burn-it-down futurism of the intelligentsia.

As the wheel of fortune turns, it lifts up the downtrodden and topples kings. The audience of Chekhov’s time didn’t have to imagine what the transition to modernity felt like—they lived in the midst of it. The emancipation of the serfs, for example, had freed Chekhov’s own grandfather. The play reflects this historical upheaval, capturing the disorientation of those who see the old order giving way to the new.

In Three Sisters, the play I discussed last week, Chekhov gives us three sympathetic characters, any of whom we might identify with. In The Cherry Orchard, however, we don’t say, “Oh, I’ve felt just like that before.” Instead, we say, “That poor woman! Can’t she see that she’s got to do something? The future will not stop for her.”

Ranevskaya’s attitude toward money strikes the modern reader as very odd. She has spent lavishly all her life. She hesitates when a neighbor asks for a loan but gives a gold piece to a passing stranger. To her, money appears and disappears like fireflies at dusk. She doesn’t treat it as something to administer; scarcity today seems unrelated to scarcity in the future, so the concept of investment makes little sense to her.

In some of his earlier plays, Chekhov spread the action over several years, showing how the passage of time changes characters. In The Cherry Orchard, however, the action unfolds over a few weeks. The characters do not grow or change. Yet time plays an even more significant role in this play than in the others. Ranevskaya reminisces about the past and acts as though still living in it. Lopakhin tries desperately to put the past behind him and think only of the future. All the characters exist in an unstable, fleeting, and anxious present.

The fourth act emphasizes this anxiety about time. The family must catch a train, and conversations grow rushed as the departure time approaches. Everyone double-checks for things left behind, and the sense of urgency grows. The play ends with mixed attitudes on display: Lopakhin rubs his hands at the prospect of his moneymaking scheme, while the family grieves the loss of their home. Some characters dread the future, some embrace it, and some shrug and walk into it. The play ends with the family departing for their new lives, leaving poor old Fiers forgotten and sick in the locked-up house.

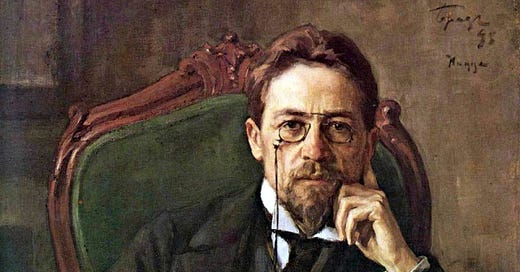

Chekhov lived long enough to see the 1904 debut of The Cherry Orchard at the Moscow Art Theater and its uneven reception in other cities—it bombed in Yalta, met frenzied acclaim in Taganrog, and had a good response from the Petersburg audiences despite hostile critics. He had struggled to finish writing it while suffering greatly from the tuberculosis that would kill him within six months of the play’s opening. In the last months of his life, he seemed to see clearly the changes the new century would bring—I don’t know how he could have written The Cherry Orchard otherwise. Although the play debuted thirteen years before the Russian Revolutions, Chekhov knew that momentous changes would soon rock his world.

Chekhov, himself a medical doctor who had seen the ravages of tuberculosis, must have known he had only months to live as he struggled to finish writing this play. Yet, like Ranevskaya, he refused to acknowledge the inevitable or even think about it. In his last letters to relatives, he kept insisting that he would recover very soon. Raymond Carver’s story, “Errand,” includes a moving account of his death—a beautiful tribute by one of Chekhov’s most inspired successors.

§ § §

With Chekhov still fresh on my mind, I think I’ll tackle a cluster of his stories next. During his lifetime, his short stories made him famous, and to say they have influenced many writers since then would badly understate matters. With many collections to choose from, I intend to make my own selection from the four-volume set published by the Folio Society. I read the entire collection in 2011, but I wrote nothing about them and I only recall that they struck me as mostly about average people who have an opportunity for an insight into themselves. Some characters reach an insight, and some miss their chance. I know a lot more about Chekhov now, and I want to circle back through his development as a master of realist fiction. When I’ve settled on a group of stories, I’ll send out a note to that effect. If you have some favorites you think I mustn’t miss, let me know.

Thank you for reading these reflections on great works of literature. I enjoy the comments I get and hope to see some suggestions for a favorite Chekhov short story you want included in my homework for the week.

Works mentioned in this post

The Cherry Orchard, in the book Five Plays: Anton Chekhov, translated by Marina Brodskaya

Anton Chekhov: The Collected Stories, translated by Ronald Hingley

“Errand,” from Where I’m Calling From: New and Selected Stories, by Raymond Carver

This is a moving account of the history of a changing culture and an artist's life. I would love to see this one on the stage.