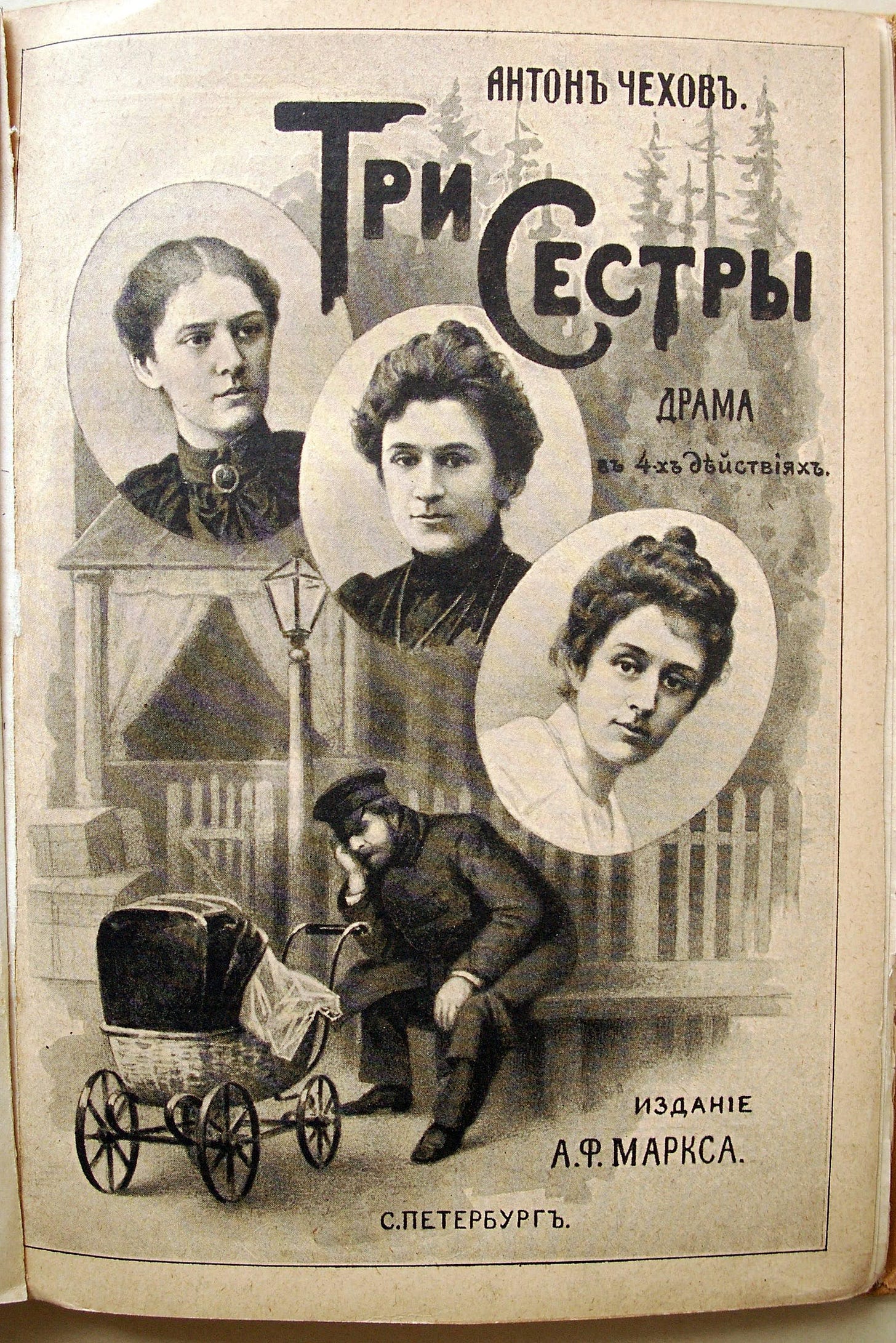

Anton Chekhov’s Three Sisters premiered in Moscow on January 31, 1901. With his earlier play, The Seagull, Chekhov had introduced a new type of play, but its initial failure in St. Petersburg convinced him to give up writing plays—and he almost did. History showed, however, that for him to succeed, he only needed a new type of stage production. Coincidentally, the newly created Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) pioneered a new type of acting, which in turn required a new type of playwright. Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko convinced Chekhov to let him and Konstantin Stanislavsky produce The Seagull in Moscow. Chekhov reluctantly agreed, and its smashing success led him to write two more plays specifically for the MAT: Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard.

What made Chekhov’s plays so different from others? Literary theorists can explain it far better than I can, but I can say what stands out to me: They have no heroes. No single character emerges as the central protagonist whose fate concerns us above all others. Although we may care more or less about individual characters, Chekhov gives us no one to idolize, nor does he provide an overarching action constituting a plot. No one strives against obstacles to achieve a goal or die trying. Instead, we encounter ordinary characters, situations, actions, and consequences, living as people do when not fictional. And while the play has a beginning and an end, that framework serves more to delineate an important phase in the history of a group than the arc of a single intention.

In much the way that European filmmakers, half a century later, rejected the hero-worship of the Hollywood star system, Chekhov at the turn of the century rejected fawning stories about czars, tycoons, political leaders, geniuses, gallants, or star-crossed lovers and offered us honest and sympathetic portraits of rural families, with all their financial insecurities, declining health, and troubled relationships.

The story of Three Sisters spans a few years, allowing us to appreciate the growth or decline of each character better than if they had merely talked about how things used to be. When the play opens, we meet the Prozorov siblings: Andrey, the brother, and his three sisters, Olga, Masha, and Irina. Although born in Moscow and raised to appreciate city life, they had moved with their parents to a small rural town, which did not seem to suit anyone’s liking. The parents had both died before the play begins, and all the siblings wish to return to Moscow, Irina most of all. However, just as so often happens in real life, these hopes keep getting put off, and time passes. Other characters interact with them, but the main family dynamic swirls around these four.

Olga, the eldest sister, never married but eventually confesses that she would have, if anyone had offered. Masha, the middle sister, did marry but has an affair with a military officer stationed in the town. The husband knows of the affair but doesn’t punish her in any way. At the end of the play, when the soldiers leave, husband and wife reconcile, and she repents of her affair, fully aware of what it could have cost her. Irina, the youngest, heeds Olga’s advice and for practical reasons becomes engaged to a much older, retired soldier whom she doesn’t love. Andrey lets his wife, Natasha, make a fool of him through her own extramarital affair and stands by helplessly as she assumes control of the family home. The four siblings exemplify very different perspectives on marriage, giving everyone in the audience a mirror into their own lives. As Donald Rayfield states in his biography of Chekhov, “The public saw their lives enacted: the three sisters stood for all educated women marooned in the provinces. [The actress playing] Masha had every unfaithful wife in the audience in tears.” Chekhov does not favor one sister over another in terms of character development. Thus, one might well consider the play’s protagonist not as one person but as the female trinity.

Andrey and Natasha serve as foils for the sisters. Natasha had a poorer upbringing than they did, and they make a few condescending remarks to her in the first act. But while we may pity her at first, she evolves into such an unsympathetic character that everyone in the audience probably thought: “Oh no, that’s not me at all, but I know someone just like her.” Andrey resembles many a weak and impractical brother but might lead the men in the audience to think, “Surely that’s not me. Is it?” Andrey and his sisters jointly own the house, but by the end of the play, he has secretly mortgaged it to pay his gambling debts.

My recent approach to literature has led me to focus more on the reader’s experience than on any message or meaning an interpretation might reveal. I feel that I’ve had moderate success with novels, but plays present a unique problem. I can’t think of playscripts as finished works of literature but rather as instructions for performing a fiction. Novels almost always reveal the thoughts of one or more characters, but performances of plays normally do not—of course soliloquies, asides, or various experimental devices constitute important exceptions. But this distinction does make a difference. The novelist addresses the reader, and between the novelist and the reader stands only the text. The book contains instructions for them to imaginatively create an extended fictional experience. The playwright also writes for an audience, namely the play’s attendees. But the actions on stage provide the instructions for the playgoer’s imagination, not the words on paper. Those words guide the actors, while the actors guide the audience. Chekhov’s words give very explicit directions but only about what to say and do. The actor’s imagination must invent the character the audience perceives.

I say all this to qualify my reflection on Three Sisters. Discussing my experience of the play resembles describing the emotions a symphony stirs in me when I’ve only seen the score but never heard it performed. Some people can do that; I can’t. Plays only fulfill their author’s intent with the help of translators, producers, directors, actors, stagehands, costume designers, and so forth.

Despite liking and admiring Three Sisters greatly, I found it extremely confusing to read. I would much rather have seen it performed. Real-life conversations involve countless interruptions, pauses, distractions, false starts, and incomplete thoughts. All these normal disturbances of conversation, absent in previous dramatic productions, get meticulously described in Three Sisters. Multiple strands of conversation overlap; offstage noises disrupt a conversation; a phrase spoken by one character prompts another to interject a line from a song or another play. What occurs quickly and naturally in real life or on stage makes for very choppy reading. The realistic scenes Chekhov invents have all the chaos of a family gathering. Actors and audiences before the time of the Moscow Art Theatre didn’t quite know how to make sense of such writing. Nowadays, everyone takes ensemble work and method acting for granted. When actors now take the stage, the audience doesn’t see them as beginning a performance but as continuing an action. Dinner conversations don’t pass back and forth between orators; they rattle along and subside. That is, characters seem to have a rich past and a future that extends beyond the stage or screen.

Of course, not everyone liked those newfangled plays of Chekhov’s. Tolstoy once told him, “Shakespeare’s plays are bad enough, but yours are worse.”

§ § §

I have a small but daunting stack of half-finished and unopened biographies in my office that I want to read before tackling another work by their subjects. So look forward in the near future to some reflections on Steinbeck’s East of Eden, Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici, some of Thomas Hardy’s poetry, and another volume of the Mahābhārata. But for the coming week, I think I’ll finish up Chekhov’s plays with The Cherry Orchard, which he wrote in the penultimate year of his short life. By the way, that small stack of biographies includes Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck by William Souder, The Strategy of Truth: A Study of Sir Thomas Browne by Leonard Nathanson, Sir Thomas Browne: A Biographical and Critical Study by Frank Livingstone Huntley, Thomas Hardy by Claire Tomalin, and Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited by Michael Millgate.

Thank you for reading the Decade Project. Your support encourages me greatly. If any of these reflections have inspired you or reminded you of how a book once made you feel, I would love to hear from you. If you have not already subscribed, please consider doing so. And if you feel like enabling this book-buying addiction of mine, you can always upgrade from a free to a paid subscription.

Works mentioned in this reflection

“The Seagull,” “Three Sisters,” and “The Cherry Orchard,” are all contained in Anton Chekhov: Five Plays, translated by Marina Brodskaya

Anton Chekhov: A Life, by Donald Rayfield

East of Eden, by John Steinbeck

Religio Medici, by Sir Thomas Browne

Selected Poems, by Thomas Hardy

Mahābhārata 4, translated by Bibek Debroy

Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck, by William Souder

The Strategy of Truth: A Study of Sir Thomas Browne, by Leonard Nathanson (out of print)

Sir Thomas Browne: A Biographical and Critical Study, by Frank Livingstone Huntley (out of print)

Thomas Hardy by Claire Tomalin

Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited, by Michael Millgate

What an interesting description of playwriting styles. I usually read Shakespeare's plays before attending a performance, but I miss a lot in the reading. I haven't read Chekhov, but now I think I will watch his plays.

Thank you. I always read a Shakespearean play, too, before attending a performance. Mostly because the onstage action goes too fast to keep up with if it's all new to me. One of these days I'll get up the gumption to have a thought or two about Shakespeare. There are sixteen of his plays on the Decade list, so that will be a real adventure. Chekhov gave very detailed directions on how actors should act. He seemed just as concerned with the pauses as a musician would be. But reading "[pauses]" doesn't convey the rhythm of an actor's pause.