The entire Mahābhārata tells the story of the Kurukshetra War, what leads to it, and what follows from it. In this volume, the war between the Pandavas and the Kouravas actually begins, with roughly the last four hundred pages taking us through the action of the first ten days.

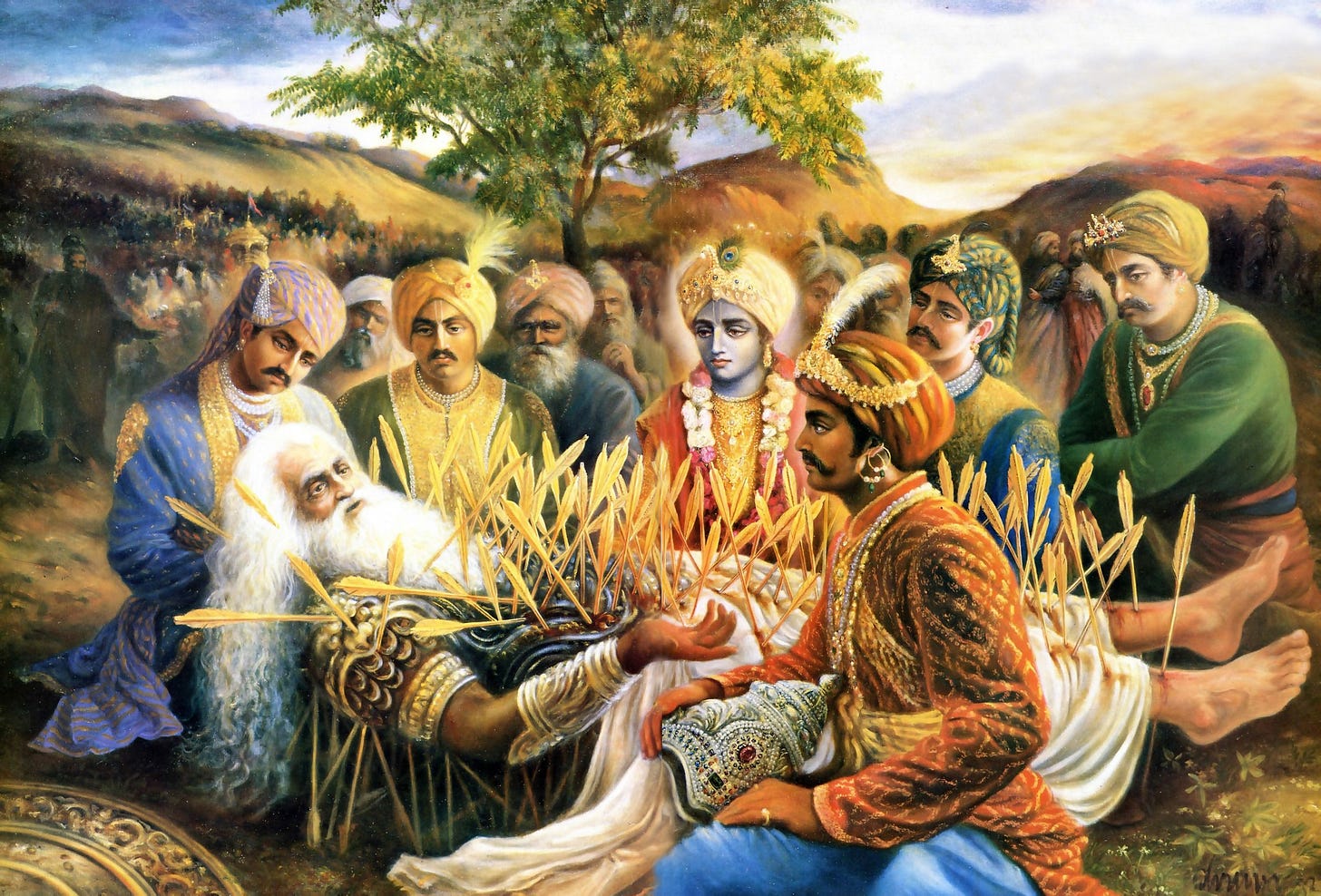

This volume revolves almost entirely around Bhishma, the military leader of the Kourava forces. No one can defeat him, not even Arjuna, but somehow he does get defeated by the end of the volume, and the leadership passes to another. We learned in the previous volume that he would not fight a woman or a woman who turned into man. It seems Bhishma had once kidnapped three sisters with the idea of marrying them off to his half brother. One of the sisters, Amba, had already arranged to marry a King Shalva. She bitches out Bhishma, saying she belongs to another, so he lets her go. But when she tries to return to Shalva, instead of welcoming her, he refuses to take her back because she had “been with” Bhishma. She insists that she is untouched, but he doesn’t care. Freed by one man and rejected by another, she had no prospects, so she vows to kill Bhishma, as the cause of all her troubles. Her woeful tale, told to the right person, wins her the boon of turning into a man—in her next life. So, in a truly gutsy move, she self-immolates and gets reborn, but, alas, as another woman named Shikhandini. Since she still can’t fight Bhishma as a woman, she schemes with a yaksha (a nature spirit) to temporarily exchange sex organs. So she changes name and pronouns from Shikhandini (she/her/hers) to Shikhandi (he/him/his). As a man now, she learns how to fight. Unfortunately, this little scheme gets discovered, and the king of the yakshas puts a curse on the yaksha, condemming her to remain a her. All this stage setting has taken place before the great Kuruksheta War begins.

One highly philosophical section occurs just before the battle commences. Yudhishthira (king of the Parvas) hesitates and looks out over the assembled armies. Remember, the leaders of both sides all have the same grandfather. Cousins will soon fight each other. Everyone knows this battle will destroy one side of the family and severely diminish the other. Yudhishthira says,

The omens that I see are ill ones. I don’t see any good that can come from killing one’s relatives in a war. O Krishna! I don’t want victory. Nor do I want the kingdom or happiness. O Govinda! What will we do with the kingdom or with pleasures or with life itself? Those for whose sake we want the kingdom and pleasures and happiness, they are gathered here in war, ready to give up their lives and their riches—preceptors, fathers, sons and grandfathers, maternal uncles, fathers-in-law, grandsons, brothers-in-law and other relatives. O Madhusudana! I don’t want to kill them, even if they kill me. […] How can we be happy after killing our relatives?

In response to this agonized cry, Krishna delivers a lecture, often excerpted and published separately as the Bhagavad Gita. Wiser scholars than I have spilt much ink over how to understand this book within a book. And since it has its own place in the Decade List, I will take it up at another time. I just want to say now that it seems to have a two-fold function similar to that of Plato’s Republic. It explores large-scale justice in war, and also small-scale justice within the soul.

This volume contains about three hundred pages that simply describe the fighting. If you read a modern account of a battle or a war, you will almost always get a description of the deployment of forces, which groups held what terrain, which units advanced, which fell back, and you always get maps to help make sense of the big picture. The Mahābhārata takes a truly microscopic approach and describes tiny scenes in isolation from the strategic plan. Take this short passage for example.

O great king! Bhishma, the grandfather of the Kouravas, pierced Arjuna with seventy-five iron arrows. O king! Drona pierced him with twenty-five arrows, Kripa with fifty, Duryodhana with sixty-four, Shalya with nine arrows and Vikarna pierced Pandava with ten broad-headed arrows. But though he was struck in every direction with sharp arrows, the mighty-armed and great archer did not suffer and was like a mountain that has been pierced.

Notice that the description states the exact number of arrows each assailant uses, their material, and their shapes. In other passages we may learn an arrow’s color and what species of bird supplied the fletching. Notice, too, that Arjuna gets pierced by 233 arrows, but doesn’t suffer a bit. At other times arrows may pierce someone who loses consciousness but the next minute jumps up and gets right back at it again, apparently fully restored, just like in a video game. Occasionally, some warrior discharges an impossible number of arrows, as when “Dhananjaya swiftly killed twenty-five thousand maharathas” (elite warriors)).

The descriptions sometimes sound apocalyptic. Here, we have a first-person account.

[He] grasped a spear that was terrible in form. It was like a flaming meteor that had been created by time itself. It blazed at the tip and covered the world with its energy. It flamed toward me, like the sun at the time of destruction.

Another description, from much later:

Many headless torsos were seen to arise from the ground, as a portent that all the beings in the universe would be destroyed.

I especially liked this one, which I’ve trimmed a bit.

With a flood of sharp arrows, Kiriti (aka Arjuna) made an extremely terrible river flow on the field of battle. […] The foam was human fat. Its expanse was broad and it flowed swiftly. The banks were formed by the dead bodies of elephants and horses. The mud was the entrails, marrow and flesh of men. […] The moss was formed by heads, with their hair attached. Thousands of bodies were borne in the flow and the waves were formed by many shattered fragments of armour. The bones of men, horses, and elephants were the stones. A large number of crows, jackals, vultures and herons and many predatory beasts like hyenas were seen to line up along its banks, as that terrible and destructive river flowed toward the nether regions.

We get detailed accounts of the action on every day. But seldom do we hear about efforts to clear the field, rescue the survivors, or bury the dead afterward. That sort of thing maybe lacks sufficient epicness. Sometimes, though, the narrator’s stance to the battle scenes has an aesthetic distance.

The earth was littered with broken chariots and shattered wheels, yokes and standards. The masses of elephants, horses and chariots were covered with blood. It looked as beautiful as an autumn sky covered with red clouds.

Animals play important literal and figurative roles in the Mahābhārata. I liked this next image a lot.

Pragjyotisha then angrily hurled fourteen javelins towards the elephant. These swiftly penetrated the excellent armour, embellished with gold, and shattered it, like serpents entering a termite hill.

We also get an occasional glimpse of the assumed cosmology. The planets and constellations are different from those of Western astrologists, of course, but I took particular note of this event.

Flaming meteors struck against the sun and suddenly fell down on the ground.

I’ve noticed in previous volumes that battles have a certain pattern to them. Everyone fights with conventional weapons—arrows, spears, javelins, clubs—for a long time; the advantage goes back and forth with neither side making a lot of progress. Eventually, though, one side gets fed up with that nonsense and pulls out a magic weapon. Most of the time, the maya weapon (illusion) determines the outcome. Someone may create the illusion that an army of demons marches toward the battlefield, for example, and the deceived enemies throw down their weapons and run away. In this battle no one pulls out a secret weapon for the first nine days.

Bhishma had already stated an important limit he placed on himself in refusing to fight a woman or woman turned man. But he had other limits, which he revealed on the ninth day of fighting.

I am incapable of being defeated in battle, even by the gods and the asuras, together with Indra. But this is when I grasp my weapons in battle and grasp my supreme bow O king! But when I cast aside my weapons, the maharathas can kill me in battle. I do not wish to fight someone who has fallen down, someone whose armour and standard have been dislodged, someone who is running away, someone who is frightened, someone who solicits sanctuary, someone who is a woman, someone who bears the name of a woman, someone who is disabled, someone who only has one son, someone who does not have a son and someone who is difficult to look at.

He sounds pretty picky to me. In any event, by revealing his fastidiousness about who he would and who he wouldn’t fight, he hands over a huge strategic advantage to the Pandavas. After nine days of fighting (stupidly, I would say), the Pandavas get smart and pull out their secret weapon: Shikhandi! Arjuna puts the trans man in front of him like some kind of human shield, and conquers the unconquerable Bhishma.

§ § §

Toward the end of this volume, it started reminding me of something. I finally made the connection with one of my favorite movies, Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, (which I strongly recommend). I can’t believe I had to read five volumes to start seeing the influence that the Mahābhārata had on Tarsem’s artistic vision. When I finish the Mahābhārata, I’ll try to say something more about the movie’s connection to it.

Next week, I’ll read a book for the in-person book club I belong to at St. Mary’s University: Karel Čapek’s novel, War with the Newts. I wrote about Capek’s play, R.U.R. last April, in case you have an interest.

All the books on my Decade Project reading list have merit, and I consider it my assignment to discover what earned them their place on it. If I do not like a book, I take that as my problem, not the author’s, so I set about fixing myself. For that reason, I refrain from boosting or panning a book, but I may offer ideas about how to find meaning in it.

Since I do not offer professional advice, I don’t hide behind a paywall; but I can always use your support for my efforts. Please consider taking out a free or a paid subscription if you don’t already have one, and, if you like what you see, tell others.

Works mentioned in this newsletter

Mahābhārata volume 5, translated by Bibek Debroy (ISBN: 9780143425182)

War with the Newts, by Karel Čapek (ISBN: 978 0 575 09945 6)

The Fall (2006), directed by Tarsem Singh

You have spoken of the foreknowledge of outcomes supplied to the reader in these volumes. What does knowing how things will turn out do to the reader's experience of the books? How is it not boring?

Thanks. I read it back in the 1970s when I worked in a bookstore and was in charge of the sci-fi section. I only remember liking the cover but being disappointed in the story. Looking forward as always to correcting my opinion.