The Holy Bible takes itself very seriously, but the Mahābhārata contains a lot of humor. I think this difference has something to do with differing concepts of time. As a child raised in a protestant home, I knew that time had one beginning and one end, and my life occupied a small piece of that finite duration. The afterlife would last forever, though, and whether I spent it in heaven or hell depended on how well I did on this one test called my life—which offered no retakes or extra credit. I think I would have turned out very differently had I grown up reading passages like this one from the Mahābhārata: “Let princes, foremost warriors, well-ornamented harlots and all the musicians go out to receive my son. Let a man with a bell quickly mount an intoxicated elephant. Let him go to the crossroads and proclaim my victory.”

At the end of the previous volume, the five Pandava brothers and Droupadi, their shared wife, completed the twelve-year exile imposed on them by the terms of the infamous dice game described in volume two. Now, only one year remains before they can reclaim their kingdom. During that one year, they must remain in hiding without anyone recognizing them. If they can do that, then the kingdom reverts to their control. In this volume, we follow first their adventures while incognito, and then their unsuccessful efforts to recover the throne peacefully. Duryodhana, the wicked cousin who has enjoyed kingship for thirteen years, does not want to give up his wealth and power. His stubborn refusal will lead eventually to the great war described in a later volume.

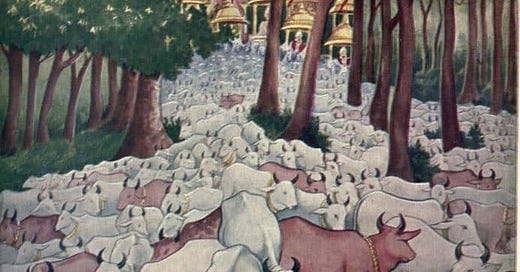

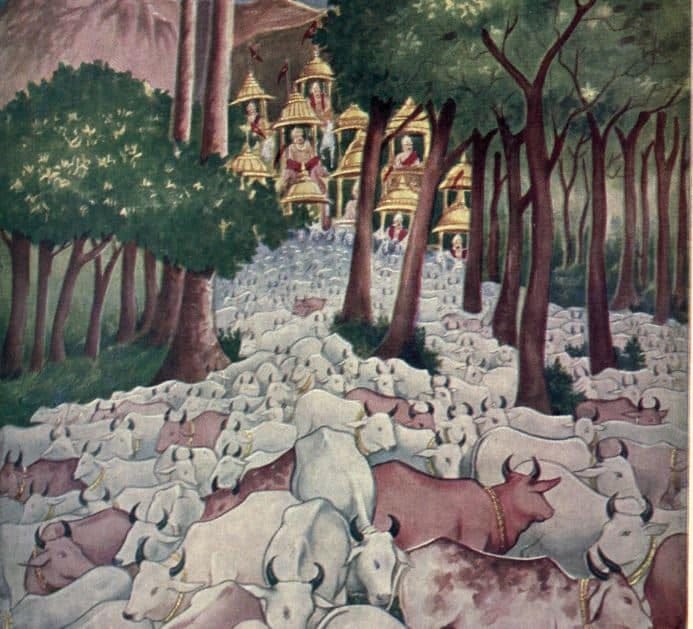

The intrepid Pandavas agree on a kingdom ruled by a certain King Virata in which to wait out the coming year. The more of the Mahabharata I read, the more it seems to resemble music than a story. This section reminds me of the scherzo of a symphony: a lighthearted interval between their deprived life in the forest and their long, frustrating negotiations prior to the battle. Having decided on a kingdom, they pick the roles they want to play. During their exile, Yudhishthira, the eldest and wisest brother whose gambling addiction brought about all their troubles, had mastered the art of winning at dice. So, somewhat ironically, he disguises himself as a professional gambler. Droupadi, the beautiful wife of the Pandavas, becomes a maidservant and hairdresser. The twins, Sahadeva and Nakula, become keepers of cows and horses respectively. Bhima, the hulk of the group, becomes a cook who wrestles. And lastly, Arjuna, the warrior hero who has mastered all known weapons both human and divine, disguises himself as a eunuch and dance instructor. Arjuna hangs up all his wonderful weapons on a tree and, for good measure, hangs a dead animal on the tree as well, to deter the curious with its stench. Thus they enter the city by separate paths and seek employment.

Rather than hide in obscurity among the rabble, the Pandavas cosplay their way into trusted positions within King Virata’s court. Of course they adopt aliases and say little about their past, but their good looks and noble bearings do provoke some suspicion. Droupadi has a lot more dignity than a mere maidservant, and Arjuna? A eunuch? Uh huh. Yet, somehow, they get themselves embedded in the center of the king’s household, with Droupadi as the queen’s personal attendant and Arjuna not only living in the harem but also serving as dance instructor to the king’s daughter.

During the year of cosplay they have a few close calls. Droupadi attracts the amorous attention of the queen’s wicked brother, for example. Calling on Bhima’s help, she agrees to act as bait for a trap, and Bhima kills the queen’s brother. Somehow despite attracting all this attention to themselves, they still manage to avoid discovery.

Meanwhile, the Kurus have started worrying. They know the Pandavas have left the forest and have hidden themselves somewhere. If discovered before a year is up, they will have to go back to the forest for another twelve years. So Duryodhana (boo, hiss) sends out spies in all directions, searching. They don’t locate the Pandavas, but they do hear about of the death of Virata’s brother-in-law. Sensing an opportunity for an evil side-quest, Duryodhana steals Virata’s cows. There follows the battle for the cattle.

The Pandavas have reached the end of their year of cosplay but they still have to take care lest they blow their cover too soon. At one point in the cattle battle, the queen’s son decides he could join in and save the day. He says, in effect, “I would fight, you know, but I don’t have a charioteer.” Droupadi, never one to put up with men’s false bravado, tells him to use Arjuna as his charioteer, which he reluctantly does. Arjuna agrees eagerly, but pretends he doesn’t know anything about shootin’ and fightin’ and such, so he puts his armor on upside down. Waving to all his new friends from the king’s harem, he rides off to battle with the prince and promises to bring back some pretty clothes for everyone. Having had his bluff called, the prince goes along for a while until he sees an enemy, whereupon he jumps out of the chariot and runs away. Arjuna jumps out, chases him across a field, and grabs him by the scruff of the neck. Duryodhana and Karna, scratching their heads and watching these antics from a distance, wonder if they might have found the Pandavas.

Finally, the thirteen-year ordeal completed, Duryodhana must give back the kingdom to the Pandavas. But he sort of likes being king, and doesn’t want to give anything back. Yudhishthira, generous and peace-loving to a fault, offers numerous compromises. Over the course of the next four hundred pages, he tries again and again to avoid the need to retake his kingdom by force. He offers to split the kingdom in half with Duryodhana. He says he and his brothers would gladly take just five villages, one for each of them. But Duryodhana interprets every concession as a sign of weakness and gets more obstinate at each step. However, as the reader has figured out, no one can play hardball with the Pandavas and survive. Bhima can bench press entire mountains, Arjuna has mastered the use of every weapon, and the gods have even lent him some magical weapons. The Pandavas have bested the Kurus in a few skirmishes already. The omens all favor the Pandavas. All of Duryodhana’s advisers tell him to compromise. Even his parents tell him to back off. But he just gets more and more determined to settle matters by a war that he and everyone else knows he can’t win.

Despite the fact that the narrators have told us over and over again how the inevitable war will end, the story in this section still has a lot of suspense. Each time a messenger goes from one party to another, each time an adviser sits down with Durydhana for a frank discussion, each new twist in the negotiations, we think, “Maybe this time,” even though we know better.

Duryodhana himself holds little interest for me, but his supporters do. The Pandavas would welcome any defector with open arms. Yet even after every friend, relative, and sage has lectured, berated, cajoled, pleaded, and warned Duryodhana, they won’t abandon him to his folly. They all opt to stay and face certain death, for an ignoble cause.

In a last ditch ploy to undermine the Kurus, the Pandavas’ mother approaches Karna, Duryodhana’s closest friend. She reveals that the sun god had fathered Karna upon her, making Karna the Pandavas’ half-brother. The sun speaks up helpfully and vouches for her. Karna says he believes her, but she had abandoned him in his infancy and the Kurus had raised him as one of their own. Therefore, his duty lies with them.

This part of the story has a more sombre tone than the previous part, as everyone tries to avert the looming war. The plot has slowed down to a crawl, but since everyone either seeks or offers advice the reader receives many instructive lessons: on leadership, on self-control, on dharma, on virtue, and so forth. And since so many formal meetings occur, we see examples of civility and courtesy between enemies.

Despite the repeated failures to influence Duryodhana, the larger narrative stays entertaining because of the numerous moralizing tales sprinkled throughout. Whenever someone wants to say this action will fail or that action will succeed, they tell a story in which someone many centuries ago tried that very action. They then point to how that story ends, and say, “See? That will happen to you.” Advice almost always comes either as such an anecdote or as a simple checklist of behaviors to avoid or to emulate. Generally friends and relatives recite the entertaining stories, and the wise sages recite the checklists. So far, I haven’t noticed that either method has had much of a persuasive effect on anyone.

At the end, one of the characters likens all humans to puppets on a string. Our leaders, our past deeds, or our desire for destiny pulls those strings, and we have each chosen one of the three as our master. We do not control our fate, yet we chose it. But, if I understand this correctly, the consequences of that choice do not haunt us for eternity. Wrong answers to the questions on this life’s test lead to more tests. And you get to take the test again and again, until you graduate.

§ § §

I mentioned last newsletter that I would tackle East of Eden next. I still plan to do that. I’ve read it at least twice before and never liked it. I don’t enjoy allegories, and I dislike stories about irredeemably evil characters. I always felt that Steinbeck’s strength as a writer lies in his realistic and sympathetic characters. But I always felt like he had funneled America’s misogyny into Cathy, the epitome of female evil, and I never saw any point to his doing that. I look forward to seeing if I can read it with a more charitable eye this time.

Thank you for reading the Decade Project. Your support encourages me greatly. If any of these reflections have inspired you or reminded you of how a book once made you feel, I would love to hear from you. If you have not already subscribed, please consider doing so. And if you feel like enabling this book-buying addiction of mine, you can always upgrade from a free to a paid subscription, no questions asked.

Books mentioned in this newsletter

The Mahābhārata, translated by Bibek Debroy

East of Eden, by John Steinbeck

This is the second work of art in a week that you compared to a symphony. :)