If I hope to read, research, reflect on, and write about one great work of literature per week, I must keep up a fairly rapid clip. Some works yield to that treatment more readily than others, but The Idiot has stubbornly resisted such an approach, not because it requires frequent pauses to absorb the beauty of lyrical passages, but simply because almost every sentence presents a stumbling block. I now believe I understand why.

Dostoevsky published The Idiot as a serialization in the Russian Messenger from 1868 to 1869, using an unusual creative process. Unlike many novelists, he did not start with the end in mind. Instead, he wanted to explore the concept of “a perfect man” in an open-ended manner. He struggled for a long time trying to decide how to go about it. He eventually created a supremely virtuous character, Prince Lev Nikolaevich Myshkin, whom he placed in his contemporary Russia among a cast of diverse and believable characters. Letting the story develop organically, Dostoevsky found that he had to adopt an unconventional approach to the narrative, which some readers may see as badly flawed. When I started reading the novel, all unsuspecting, I had so many objections and questions that I began to doubt its literary merit. Over time, however, it made more sense, and I now appreciate the courage it took on Dostoevsky’s part and on the part of his publisher to follow through to the end. To me, in short, The Idiot makes the best sense if appreciated not as a traditional novel but as a philosophical thought experiment.

In a thought experiment, as described in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “we visualize some situation that we have set up in the imagination; we let it run or we carry out an operation; we see what happens; finally, we draw a conclusion.” You might think we could learn nothing about the world by simply imagining things. Can’t we just imagine anything we want? Interestingly, though, as many authors know, our imagination can surprise us. To quote the same source, “Once a scenario is imagined it may assume a life on its own, and this explains partly the creative power of a good thought experiment.” This, I believe, explains Dostoevsky’s purpose in writing The Idiot. He wanted to know if Christian virtue alone could save the world. So he imagined a perfectly virtuous person, put him into the contemporary world, and watched what happened.

To show how this method resulted in stumbling blocks for my reading, I’ll mention some of the things that most bothered me. First, another writer might say, “George muttered under his breath, ‘Over my dead body!’” But Dostoevsky would write, “’Over my dead body!’ muttered George under his breath.” In other words, he leads with the words and follows with the manner of delivery. This difference might seem trivial, but it stops me after I’ve imagined a shouted “Over my dead body!” and forces me to reimagine the line as quietly muttered. Such mental revisions, when made line after line, add up to a very rough reading experience.

Second, every character’s emotional state bounces around wildly. I soon gave up predicting how a character would deliver his or her lines, as they may flip polarity within the same breath. I would thus end up taking two to three times longer than usual to work my way through the often scatterbrained conversations.

Third, along with giving the characters mercurial emotions, Dostoevsky exaggerates their actions. I think the word “suddenly” appears more times per page in this book than in any other book I’ve read. Seated people suddenly jump up and shout. Standing people suddenly collapse into chairs and weep. Everyone flaps their arms.

Dostoevsky also seems to delight in turning everything into a mystery. One favorite technique consists in predicting that something will soon happen, and letting the reader know in advance how to feel about it. Two near random examples should make the point.

He suddenly sat down unceremoniously and began telling the story. It was very incoherent; the prince frowned and wanted to leave, but suddenly a few words struck him. He was struck dumb with astonishment … Mr. Lebedev had strange things to tell.

Yes, he uses “suddenly” twice. In this next example, he anticipates the unexpected.

But here an incident suddenly occurred and the orator’s speech was interrupted in the most unexpected way.

It bothers me when authors bully me into having an emotion, but I have no idea what to think in cases like the above when they tell me what I should feel. Vladimir Nabokov, in discussing The Idiot in his Lectures on Russian Literature, puts it this way, “[T]he plot itself is ably developed with many ingenious devices used to prolong the suspense. Some of these devices appear to me, when compared to Tolstoy’s methods, like blows of a club instead of the light touch of an artist’s fingers...”

The eccentricities in The Idiot bothered me, as they bothered Nabokov, for a long time. But I now think they arose because of the experimental nature of Dostoevsky’s writing. After having written Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky could have concluded that atheism’s failure proves the superiority of a Christian morality. But he still had doubts. Would Christlike virtue really lead to anything better than atheistic thinking does, even in this messed up world teeming as it does with selfish, scheming, and petty people? Maybe, but maybe not. A perfectly good person would always treat others with honesty, empathy, acceptance, and forgiveness; in other words, everyone would think of such a good person as some kind of idiot. OK. That gives us the novel’s title, but now what? A real thought experiment must delve deeper than that. So Dostoevsky imagines a menagerie of Russian characters for the prince to engage with, and, in the true philosophical spirit of a thought experiment, he lets the stories all play out without prejudging the outcomes. As the novel progresses, we observe the effect of perfect love and forgiveness on each of these flawed people.

Dostoevsky serialized this novel without a clue as to how it would end. The story actually told itself. The characters, not Dostoevsky, made all the choices. If he had planned it out in advance, he would have created two-dimensional characters to move the plot along as needed. He would have written a dull Christian allegory. Instead, he makes all the characters with good and evil in them, just like real people, and more often than not, the good in each person emerges in response to the good that Myshkin shows them.

What I’ve said so far doesn’t explain the stylistic oddities. For that, we need to recognize the role of the narrator. The narrator has just as real a personality as any other character in the novel, but he doesn’t know what will happen from one minute to the next any more than Dostoevsky does. How does an omniscient but mystified narrator tell a story? Well, probably like when poor Dad gets trapped into telling a bedtime story and has to make it all up as he goes along, hiding his uncertainty with mystification and dramatic pauses. Once I recognized the ineptitude of the narrator, I could dismiss the idea that Dostoevsky simply wrote poorly. After all, I don’t remember Crime and Punishment bothering me in the same way. The narrator of The Idiot sits me down and starts spinning a yarn that might never end. Trapped in a story he never made, the narrator must resort to hemming and hawing at important decision points in the story. Once I understood my relationship to the narrator this way, I started to have a lot more fun.

At the beginning of the novel, Prince Myshkin has left a sanatorium in Switzerland where he had undergone a long, unsuccessful treatment for epilepsy. Traveling by train to St. Petersburg, he meets two people: Rogozhin and Lebedev. Rogozhin reveals that he plans to see a certain Nastasya Filippovna with whom he has become infatuated. Myshkin also has some business to take care of in St. Petersburg. First, he wants to meet a distant relative, Elizaveta, to whom he had previously written but has received no response. Second, as we only learn later, he hopes to claim a sizable inheritance. At the novel’s beginning, however, he has no money at all. Upon his arrival, he goes to the office of Elizaveta’s husband, General Epanchin, who decides to help him out with a place to stay. He sends Myshkin to the house of his aide, Ganya. Several people live in the house, and it turns out Ganya hopes to marry the same Nastasya Filippovna that Rogozhin had previously mentioned on the train ride.

Nastasya Filippovna’s dark and astonishing beauty captivates Myshkin, just as it captivated Ganya and Rogozhin, but, when the prince gets to know her better, he feels immense pity for her as she oscillates between contempt for others and for herself. Orphaned in infancy and sexually abused by her guardian, she finds it impossible to have a simple, loving relationship with anyone. Society sees her as a “fallen woman” but her abuser has offered a great dowry to get her married off and out of his guilt-ridden sight. So a major dynamic soon becomes clear: Ganya has proposed and awaits her decision, while Rogozhin intends to possess her no matter what the cost. She can’t decide who she deserves most, but then “suddenly” Myshkin falls under her spell. Yikes!

Part One ends with Nastasya’s riotous birthday party, where she has promised to reveal her decision regarding Ganya’s proposal. She knows all too well that her suitors see her as nothing but a commodity up for auction to the highest bidder, and everyone else sees her as a kept woman, so she feels she has no human dignity and compensates with haughty pride. She treats her fawning suitors with contempt and looks at herself in disgust. But Myshkin assures her that she does indeed have dignity and worth, that her outrageous behavior has a cause, “You may be so unhappy that you actually consider yourself guilty.” Then he, too, offers to marry her. From that moment on, Nastasya’s indecision about whether and whom to marry tears her apart and can only end badly.

The plot, if one could call it that, revolves around Myshkin’s off-again on-again relationship with two women, Aglaya Epanchin (General Epanchin’s daughter) and Nastasya Filippovna. Myshkin clearly prefers Nastasya, and she loves him, but she feels she does not deserve his love. Despite twice agreeing to marry him, she runs away both times with Rogozhin. Nastasya, certain that Myshkin deserves someone better, tries to play matchmaker to him and Aglaya. Myshkin loves both women, but not in an erotic sense. He loves them because they need love, and he has more than enough to offer them. While this waffling of marriage promises may constitute a plot, the success of Dostoevsky’s thought experiment depends on how Myshkin deals with the other ego-driven characters. They all struggle with mortality in their own way, and their interaction with Myshkin’s kindness produces a variety of unpredictable outcomes. These smaller interactions make up the bulk of the novel.

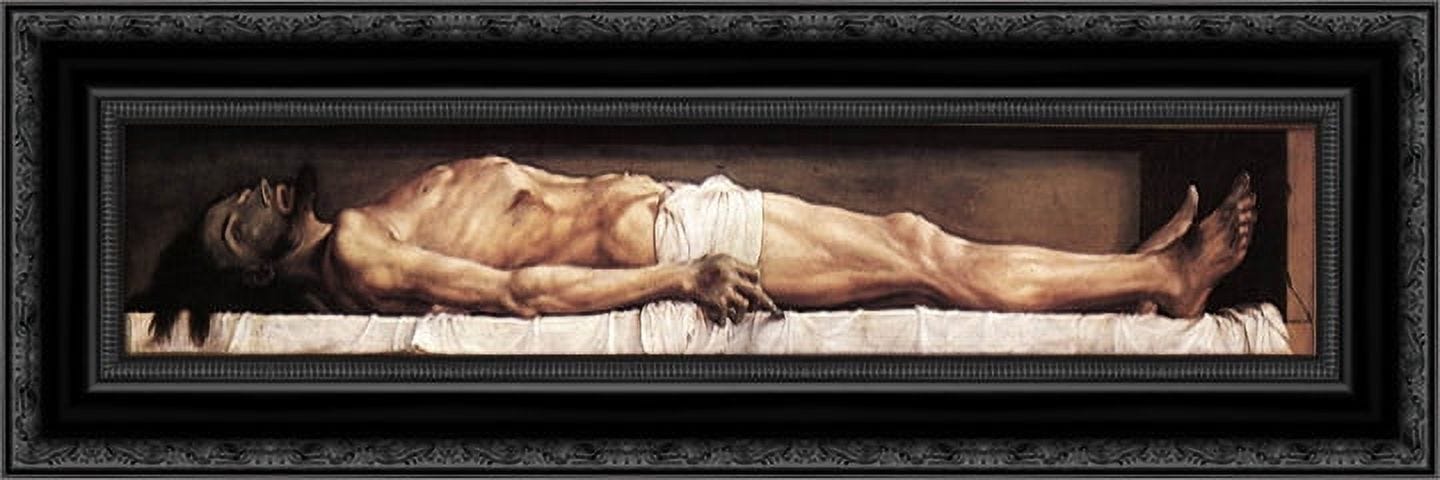

One image gets special attention, and I think it captures the doubt underlying Dostoevsky’s experiment. Rogozhin owns a reproduction of a painting, sometimes referred to as The Dead Christ, by Hans Holbein the younger (1497-1543).

The image haunted Dostoevsky for its stark depiction of a merely human corpse, broken and rotting, with no divine glow or suggestion of immortality as one usually sees in religious paintings. Myshkin and Rogozhin discuss it at great length as it relates to Rogozhin’s crisis of faith. Even the body of Christ decays. Faith, Dostoevsky seems to say, has a lot to do with whether that fact matters. Myshkin thinks it does not.

In all the references I have seen to The Idiot, I have not seen much mention of humor. And the vague awareness I had that things would end badly didn’t lead me to expect any. But time after time I found myself laughing out loud at some of the lurches the story took. A couple of examples might help. About halfway through, Dostoevsky has a band of four new characters show up, including a nihilist or two. Three of the group briefly introduce themselves to the prince, then the fourth one does so.

“Ippolit Terentyev,” the last one shrieked in an unexpectedly shrill voice. They all finally sat down in a row on chairs opposite the prince; having introduced themselves, they all immediately frowned and, to encourage themselves, shifted their hats from one hand to the other; the all got ready to speak, and they all nevertheless remained silent, waiting for something with a defiant air, in which could be read: “no, brother, you’re not going to hoodwink me!” One could feel that as soon as any one of them began by simply uttering a single first word, they would all immediately start talking at the same time, rivaling and interrupting each other.

Somehow, I couldn’t take these guys seriously. In fact, they struck me as about as pathetic as the nihilists in The Big Lebowski. And for that matter, couldn’t the idiot prefigure the Dude? And didn’t the cowboy storyteller at the bar give a good imitation of Dostoevsky’s bumbling narrator? But I digress.

Of all the minor characters, I liked Myshkin’s fellow lodger, a General Ivolgin, the most. He spins absurd tales about himself to establish a bond with the person he’s talking to. In this passage, he has just introduced himself to Prince Myshkin.

“...Your name and patronymic, if I dare ask?”

“Lev Nikolaevich.”

“So, so. The son of my friend, one might say my childhood friend, Nikolai Petrovich?”

“My father’s name was Nikolai Lvovich.”

“Lvovich,” the general corrected himself, but unhurriedly and with perfect assurance, as if he had not forgotten in the least but had only made an accidental slip. He sat down and, also taking the prince’s hand, sat him down beside him. “I used to carry you about in my arms, sir.”

“Really?” asked the prince. “My father has been dead for twenty years now.”

“Yes, twenty years, twenty years and three months. We studied together. I went straight into the military … “

“My father was also in the military, a second lieutenant in the Vasilkovsky regiment.”

“The Belomirsky. His transfer to the Belomirsky came almost on the eve of his death. I stood there and blessed him into eternity. Your mother … “

The general paused as if in sad remembrance.

“Yes, she also died six months later, of a chill,” said the prince.

“Not of a chill, not of a chill, believe an old man. I was there, I buried her, too. Of grief over the prince, and not of a chill. Yes, sir, I have memories of the princess, too! Youth! Because of her, the prince and I, childhood friends, nearly killed each other.”

The prince began listening with a certain mistrust.

Dostoevsky has packed this novel with so many characters, each struggling with their absurd existence, each one alternately droll and pathetic, that a reader could easily lose sight of the question driving the thought experiment. One might expect a purely good person, plopped into the modern world, to attract purely evil people who take merciless advantage of him. Instead, everyone Myshkin meets has a moral complexity about them, and they respond well to pure goodness when they meet with it. If someone insults, slaps, threatens, or cheats him, Prince Myshkin does not respond in kind or even take offense. He laughs or apologizes or even defends his attacker. He recognizes the meanness in others, but also sees the good in them or the hurt that drives their meanness. He never lies; he lets would-be enemies know that he understands their enmity but also why they feel the way they do. By his accepting others and forgiving them, he totally disarms them. Anyone who starts off determined to hate him ends up loving him, and feeling ashamed of their own pettiness.

A traditionally plotted story about a modern-day Christlike figure would probably have ended with the execution of the new Christ. That does not happen. Though tragic, the ending unfolds not as a plot-driven denouement, but as a character-driven catastrophe. Because Prince Myshkin’s goodness does not exceed the humanly possible, because he cannot rise to the level of divinity, he collapses from the unendurable burden of loving all who need love and forgiving all who need forgiveness. His epilepsy returns; he goes mad and gets sent back to the sanitorium. Everyone soon forgets him.

So how does the thought experiment turn out? Inconclusively, I would say. While interacting with the prince, most characters do indeed rise above themselves. They do not crucify him, as we might expect; but neither do they undergo a moral conversion. Like a sonic boom, he rattles their emotional windows, but his effect quickly fades, leaving them to resume their petty, grasping, mean-spirited lives. Virtue alone can accomplish very little. Even the body of Christ decays.

I don’t know if I believe my own explanation of Dostoevsky’s apparent “blows of a club.” I think everyone agrees that he violates many norms of good writing in this novel. I just don’t know whether to praise these violations, condemn them, or make excuses for them. But I do know that I want to dig deeper. So I plan to read Joseph Frank’s five-volume biography of Dostoevsky as well as The Possessed (or The Demons). I also plan to reread the works I thought I had checked off my list years ago: Crime and Punishment, The Brothers Karamazov, and Notes from Underground. This undertaking won’t happen overnight, so expect to see more about Fyodor at odd intervals over the next months.

In the meantime, I’ll try to finish up volume five of the Mahābhārata for next week.

§ § §

I consider myself a devoted reader, not a writer or critic. I do not sell books, recommend them, or judge them. I only try my best to understand them and describe my efforts at understanding. It cheers me greatly to think that someone else benefits from these efforts.

Since I don’t like the idea of a paywall, I don’t hide behind one; but if you want to support my literary struggles, please take out a free or a paid subscription and receive every new reflection as I post it.

Works mentioned in this post

The Idiot, by Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Notes from Underground, by Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Possessed (or The Demons), by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Crime and Punishment, by Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Big Lebowski, directed by Ethan and Joel Coen

Dostoevsky (in five volumes), by Joseph Frank

Lectures on Russian Literature, by Vladimir Nabokov

Mahābhārata 5, translated by Bibek Debroy

I was reading this at mainly the same time as you, and it took me (significantly) more than a week as I took it in bite sized chunks every day. I largely agree with your assessment: The novel is a thought experiment and a philosophical inquiry. And the interest lies in the characters and how they react to Myshkin. And it succeeds on that level

While agreeing with you that a purely "Christ-like" depiction of Myshkin would not have worked as well as a man with some flaws. However, knowing that this was to be Dostoyevsky's depiction of "the perfect man", I still found some of Myshkin's actions less than satisfying. As the novel went on, particularly with regards to how he navigated the two love interests, he struck me as too weak, indecisive and passive to be in any way considered "perfect".

Can I ask what translation you used? I read Constance Garnett, and I have usually been satisfied with her work: In this case, I found the novel slow-going and sometimes confusing. But I don't know how much of that is Dostoyevsky and how much Garnett (and how much simply my own limited abilities). I was able to blaze through her Brothers Karamazov, but not her Idiot. When I turn to The Possessed, and eventually a reread of Crime and Punishment, I may give another translator a chance, but I'm not sure who yet.

Interesting read!! Enjoyed it 😀👌