The Epic of Gilgamesh—translated by Benjamin R. Foster

The tavern keeper at the edge of the world

The Epic of Gilgamesh opens with a startling prologue in which the narrator, instead of calling on a goddess or a muse to inspire his words, speaks directly to the reader. He extols the life and wisdom of Gilgamesh, and then walks the reader around the walls of Uruk, as on a tour. Look over here, he suggests, and over there, pointing proudly:

Mount the wooden staircase, there from days of old,

Approach Eanna, the dwelling of Ishtar,

Which no future king, no human being can equal.

Go up, pace out the walls of Uruk.

Study the foundation terrace and examine the brickwork.

Is not its masonry of kiln-fired brick?

And did not seven masters lay its foundations?

One square mile of city, one square mile of gardens,

One square mile of clay pits, a half square mile of Ishtar’s dwelling,

Three and a half square miles is the measure of Uruk!

He then directs the reader to open the great cedar box in front of them, take out the tablets inside, and read the story of Gilgamesh.

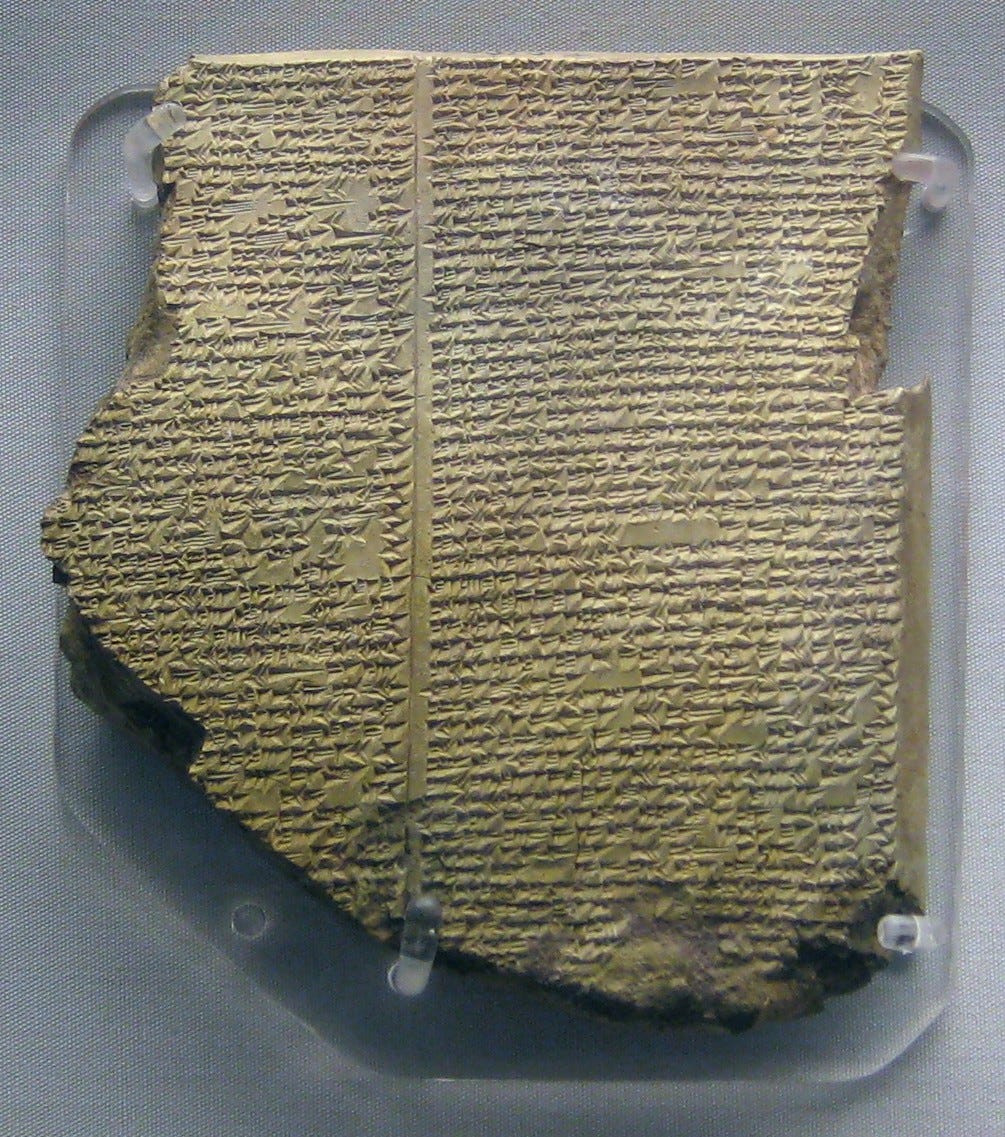

The story unfolds in eleven tablets, with many lacunae. This amazing epic tale, composed over forty centuries ago predates all others. The scholars who have collected the various pieces of the story from retellings or expansions by the Gilgamesh fan fiction community of antiquity have done an amazing job of recovering a relatively complete version of the story, but it obviously called for much educated guesswork. The story about recovering the epic could have made its own epic. So, I didn’t get caught up in that and simply experienced the story as a story.

Tablets I through VII tell of the friendship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu and their heroic exploits together. The gods created Enkidu to fight with Gilgamesh, a typical alpha male jerk, and take him down a notch. They fought, and Enkidu won, but they became inseparable buddies after that. These tablets contain typical epic stuff: the origin of Enkidu, the killing of the monster Humbaba, the defeating of the Bull of Heaven. You know, the usual epic hero things.

Not surprisingly, these two lost boys get pretty full of themselves and offend the gods. So Enkidu must die. Tablet VII ends with Enkidu’s death, oddly enough, not in heroic combat, but after twelve days of illness. In tablet VIII, Gilgamesh laments the death of his friend and buries him in style. These first tablets, while containing a few surprises, have mostly dished up standard epic fare. But tablet IX starts down a very different path. After lamenting Enkidu’s death, it dawns on Gilgamesh that he too must die. Like most of us humans, however, he refuses to accept his own mortality. He sets out instead to find the secret of eternal life. Utanpishtim, the survivor of a great flood that killed all the rest of humanity, has become an immortal while remaining human. Gilgamesh hopes to learn the secret from him. Unfortunately, he lives in the remotest of all places on Earth. Thus, Gilgamesh begins a final quest, alone.

Utanipishtim lives beyond the western edge of the Earth, so Gilgamesh must go to the westernmost part of the land, where the sun goes down. That somehow involves racing the sun. It seems the sun travels across the sky in the day, but travels back to the east through a tunnel between two mountains at night. Sort of like the ball conveyor at a bowling alley. A scorpion monster guards the eastern entrance and tells Gilgamesh he can’t go in there. But Mrs. Scorpion monster takes pity on him and convinces Mr. Scorpion monster to give Gilgamesh a chance. Gilgamesh and the sun start out, the sun racing across the sky and Gilgamesh dashing through the cave. Amazingly, he makes it all the way through before the sun can enter the western end of the tunnel and burn him up.

In tablet X, a tired and grungy Gilgamesh starts wandering around in the western land. There, he meets Siduri, a female tavern keeper, who doesn’t trust him and doesn’t believe his story at first. He doesn’t much look like a king, all dusty and everything. When he convinces her of his identity and of his quest, instead of falling down in praise, she tells him to get over himself:

Gilgamesh, wherefore do you wander?

The eternal life you are seeking you shall not find.

When the gods created mankind,

They established death for mankind,

And withheld eternal life for themselves.

As for you, Gilgamesh, let your stomach be full,

Always be happy, night and day.

Make every day a delight,

Night and day play and dance.

Your clothes should be clean,

Your head should be washed,

You should bathe in water.

Look proudly on the little one holding your hand,

Let your mate always be blissful in your loins,

This, then, is the world of mankind,

He who is alive should be happy.

Spoken like a true tavern keeper. At one time in his life, he would have gladly accepted her advice. But not now.

Gilgamesh said to her, to the tavern keeper:

What are you saying, tavern keeper?

I am heartsick for my friend.

What are you saying, tavern keeper?

I am heartsick for Enkidu!

At this point, I thought, “Haven’t I played this video game before? A tavern at the edge of the world? Really? Should I expect a helpful owl or wolf to guide him to the abode of Utanpishtim?” Sure enough, Siduri tells him to find the boatman, Ur-Shanabi, who will ferry him across the great water. This he does and the two of them arrive after a difficult journey. Unfortunately, Utanpishtim, while immortal, can’t offer a guide for achieving immortality. He had only lucked into immortality because of a squabble among the gods, and so he has no self-help advice for aspiring immortals.

So that ends the quest—or does it? Gilgamesh starts heading back to Uruk in dejection with the same boatman, but Mrs. Utanpishtim takes pity on him and tells him about a magical plant that will restore his youth. Gilgamesh would prefer never aging, but rejuvenation will do, he thinks. He gets the plant and heads back to civilization triumphantly. But then—and you knew this would happen—tragedy strikes. He takes a little nap and a snake steals the plant.

I can see it now, the snake slithering away with a wheezing laugh and leaving its old skin behind it. Gilgamesh realizes what has happened, and he knows he can blame no one but himself.

Thereupon Gilgamesh sat down weeping,

His tears streaming down his face.

For whom, Ur-Shanabi, have my arms been toiling?

For whom has my heart’s blood been poured out?

And then come the best lines in the whole epic:

For myself I have obtained no benefit,

I have done a good deed for a reptile!

Gilgamesh has finally reached the end of the trail. All his questing and gallivanting across creation accomplished no more than helping a stupid snake shed its skin! What can one do but laugh?

After that supreme irony, the poem concludes quickly, with Gilgamesh returning to Uruk, to stand beside the walls of his grand city. The poem concludes in the same place it began. But the chastened Gilgamesh who contemplates the walls of Uruk, sees them differently than before. He has metaphorically shed his own skin. He escorts the boatman, Ur-Shanabi, to Uruk, and urges him to admire this marvel of human creation. He uses the same words the narrator used to address the reader in the first tablet:

Go up, Ur-Shanabi, pace out the walls of Uruk.

Study the foundation terrace and examine the brickwork.

Is not its masonry of kiln-fired brick?

And did not seven masters lay its foundations?

One square mile of city, one square mile of gardens,

One square mile of clay pits, a half square mile of Ishtar’s dwelling,

Three and a half square miles is the measure of Uruk!

And thus ends the epic of Gilgamesh. Sort of. Gilgamesh still lives in this tale that has somehow endured for four millennia, broken and scattered but stitched together from Babylonian, Sumerian, and Hittite fragments. The walls of Uruk of which the mortal Gilgamesh took such pride still stand in Iraq. You can go for yourself to study the foundation terrace, examine the brickwork, marvel at the kiln-fired brick masonry, and dream of life everlasting.

Gilgamesh was the first figure in literature to seek immortality, but by no means the last. From Tithonus to Ponce de León to Dorian Gray to Lazarus Long, stories about eternal life in the here and now have occupied a significant part of our Western literature. Many stories of those who don’t or can’t die serve as cautionary tales. The terrible price or consequences of immortality form the basis of many horror stories. But Gilgamesh fails, and he weeps when he realizes he has lost his only chance. With what attitude did he then return to Uruk? We get no direct answer; he only shows the city to Ur-Shanabi for him to admire. But if we go back to the prologue, we see these lines about the great man Gilgamesh, which we might have missed the first time:

He saw what was secret and revealed what was hidden,

He brought back tidings from before the Flood,

From a distant journey came home, weary, but at peace.

“Weary, but at peace.” He has still not accepted the advice of Siduri, the tavern keeper,

As for you, Gilgamesh, let your stomach be full,

Always be happy, night and day.

Make every day a delight,

Night and day play and dance.

Siduri tells him he should seek pleasure and have fun. Laugh and laugh and laugh like the beautiful people in a cheap wine commercial. Gilgamesh could not go back to that sort of life. Not after what he had seen. Not after the death of his dearest friend. In his journey, he had spied on the hidden and talked to the past. He had drawn a breath of such wisdom as life can offer, he had built strong walls around a great city, and he could now know peace. He had done things worth doing.

§ § §

My RL book club will take up Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse sometime this year, so I think I’ll read that next. Back in October, 2024, I offered some thoughts about Mrs. Dalloway, so this will give me another chance to enjoy one of my favorite literary stylists.

Welcome to all the new arrivals at The Decade Project. I hope you enjoy what you find here. I won’t fill up your inbox every day, so don’t worry about that. I can only handle one book and one post per week. For those who have already traveled with me awhile, thank you for your loyalty. I have training as a philosopher, not as a literary critic, and my reflections reflect that fact. So I don’t pretend to write reviews or summaries. I just read and share my thoughts and reactions.

I greatly appreciate your support of my project. While I don’t ever plan to hide behind a paywall, please consider taking out a paid subscription if you don’t already have one. And if you like what you see, tell others.

Works mentioned or alluded to in this post

The Epic of Gilgamesh, in the second Norton Critical Edition, translation by Benjamin J. Foster

“Tithonus,” by Alfred Lord Tennyson

The Picture of Dorian Gray, by Oscar Wilde

Methuselah’s Children, by Robert Heinlein (and other books featuring Lazarus Long)

Mrs. Dalloway, by Virginia Woolf

To the Lighthouse, by Virginia Woolf

Timely, since the world is currently having it's own existential crisis. Ernest Becker convinced me years ago that everything humans do is about either fear of or denial of death.

Hi Robert,

I remember reading Gilgamesh a few years ago, and being impressed by the fact that it didn't have a "happy" ending. I like your explanation of the ending/meaning.