Chief Bromden, a long-time inmate in the unnamed hospital’s psychiatric ward, tells the story of the events after Randle McMurphy arrives, swaggering, laughing, bragging, and loud. Nurse Ratched, often called “The Big Nurse,” and her staff have long kept the inmates docile with a combination of shame, force, drugs, electroshock treatments, and, as a last resort, prefrontal lobotomies. Chief Bromden has learned to play deaf and dumb, thus avoiding all attention. But he suffers from hallucinations and paranoia, so the Big Nurse keeps him doped up all the time. In his paranoia, he believes a huge, mysterious machine he calls the Combine completely controls the thoughts and actions of him and everyone else.

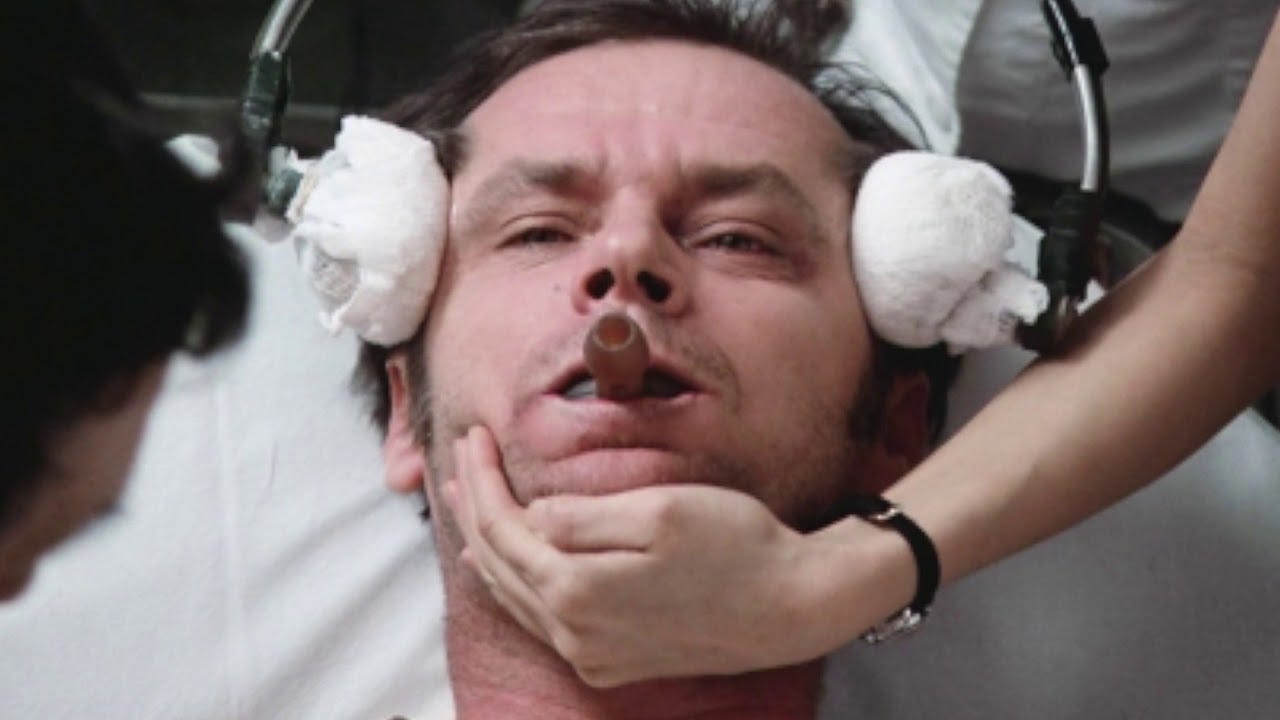

McMurphy’s arrival initiates a conflict of wills between McMurphy and the Big Nurse, which escalates through distinct phases until reaching the only possible conclusion. He begins a campaign of insubordination and mockery, in which he scores small successes and suffers small setbacks; however, she always retains the upper hand, because the duration of McMurphy’s stay in that ward depends entirely on her orders. She has him under her control until she decides to release him, and she can afford to wait patiently as long as it takes for him to submit. But of course, if it looks like she will lose that game, she can always order him turned into a vegetable. In 1962, when this novel appeared, lobotomies had fallen out of favor. But that didn’t stop the Big Nurse from ordering them.

Very early in the novel Bromden describes Nurse Ratched and indicates her resentment at being a mere human.

She nods once to each [inmate]. Precise, automatic gesture. Her face is smooth, calculated, and precision-made, like an expensive baby doll, skin like flesh-colored enamel, blend of white and cream and baby-blue eyes, small nose, pink little nostrils—everything working together except the color on her lips and fingernails, and the size of her bosom. A mistake was made somehow in manufacturing, putting those big, womanly breasts on what would of otherwise been a perfect work, and you can see how bitter she is about it.

She values the hospital regimen more than anyone should, so she can permit no divergence from the routine. Thus, when she sees three attendants gathered in a group, talking instead of working, she calmly requests that they go about their assigned tasks. However, Bromden describes this cordial, chilly encounter in hallucinatory terms.

She’s swelling up, swells till her back’s splitting out the white uniform and she’s let her arms section out long enough to wrap around the three of them five, six times. She looks around her with a swivel of her huge head. … So she really lets herself go and her painted smile twists, stretches to an open snarl, and she blows up bigger and bigger, big as a tractor, so big I can smell the machinery inside the way you smell a motor pulling too big a load.

Call this foreshadowing, if you wish. We quickly learn that Bromden’s hallucinations expose the inhuman, violent reality lurking just beneath the placid surface of orderly routines.

McMurphy thought himself clever for feigning insanity to escape from the Pendleton Work Farm, expecting to find an insane asylum easier to handle than hard labor in prison. When he learns about the reality of his situation, however, he decides to play by the hospital’s rules, seeing submission as the only way out. But Cheswick, one of the other inmates, emboldened by McMurphy’s previous insurrection, tries to protest the rationing of cigarettes. Without McMurphy’s support, though, his little revolt fails. After he returns from being “adjusted,” he drowns in the hospital pool, a possible suicide. McMurphy, seeing that Cheswick and others have adopted him as a leader, begins to feel a greater responsibility. The death of Cheswick marks McMurphy’s transitions from hero to savior.

The middle of the twentieth century saw the elevation of capital-S Science to the level of divinity, with scientists serving as its high priests. The so-called golden age of science fiction produced utopian fantasies of how Science would change our lives: eliminating disease, hunger, poverty, housework, and labor. One part of that fantasy involved “fixing” the flawed human mind. The promises of a paradise on Earth didn’t appeal to everyone, however. If Science could manufacture anything, it could take a shortcut to pacifying humanity and simply manufacture happiness in the form of a pill, as happens in Huxley’s Brave New World. Or pacify us with brainwashing techniques that make us believe ourselves happy, as happens in Orwell’s 1984. In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Science could readjust the brain permanently. As Chief Bromden explains,

The ward is a factory for the Combine. It’s for fixing up mistakes made in the neighborhoods and in the schools and in the churches, the hospital is. When a completed product goes back out into society, all fixed up good as new, better than new, sometimes, it brings joy to the Big Nurse’s heart; something that came in all twisted different is now a functioning, adjusted component, a credit to the whole outfit and a marvel to behold.

Distrust and disaffection with the promises of science had built up after World War II, and erupted into full-blown rebellion in the ’sixties. For that reason, Cuckoo’s Nest strikes me as the perfect novel for the its time. It captures the paranoia, the rage against the machine, the institutional use of mind-altering drugs, the resistance to authority, the Freudian creed, the belief that “what the world needs now is love sweet love, that’s the only thing there’s just too little of.” It also captures the racism, the misogyny, the anarchic deviltry. At that time, we railed against the military-industrial complex. We protested the war in Vietnam. We flaunted every societal convention. We experimented with drugs, sex, and mysticism. We shook our collective fists at The Establishment, that evil alliance between the government and industry, bent on turning us all into cogs in the great wheel of science-driven bureaucracy. We sought individual freedom at all costs. Kesey captures this ethos perfectly, and this novel probably did a lot to give it a place in our collective imagination.

Unfortunately, the novel could end only one way: McMurphy had to die. You can’t fight the establishment with any hope of winning. At best, you can expose the brutality hiding just below the surface of its silly rules and regulations. Bureaucracy puts on a benign and friendly face until you start to resist, and it doesn’t take much resistance for the gloves to come off. McMurphy resisted, as did my generation. McMurphy got a lobotomy in 1962. We got Kent State in 1970. Kesey tells more than a story. He taps into the central archetype of a whole generation, and he foretells the inevitable outcome.

But that archetype did not vanish with Kent State. Today’s rampant conspiracy thinking—the anti-vax movement, Q-Anon, and all the rest—only repackages our own paranoid mythology for a new generation. Orwell’s Big Brother, Chief Bromden’s Combine, The Chicago Seven’s Establishment, MAGA’s Deep State—all the same archetype, and all the same ending: “Resistance is futile.” For the last century we have lived in a world we feel to be vast, malevolent, and increasingly beyond our control. We live out our lives like Chief Bromden, keeping as low a profile as possible to avoid getting caught and crushed in the implacable clockwork of modernity. The mistake we have made this century involves giving implacable Fate a name and a face. McMurphy thought he had a conflict with a nurse. Had that been true, he might have won. Chief Bromden knew better, he knew that McMurphy only beat his little fists uselessly against a vast machine that consumed humanity one soul time.

Ken Kesey’s resolution offers no real hope. The ultimate cure for all human ills? More sex. Not just more sex, but male-female sex and a world in which men are in charge. Every psychological problem in Cuckoo’s Nest seems due to a perversion of the “natural” dominance of men over women. When women call the shots, Kesey seems to say, nature afflicts men with neuroses or psychoses and the Combine reaps another soul. But really, thinking we can save humanity by converting to a me-Tarzan-you-Jane world seems as ridiculous as thinking we can save ourselves by popping the right collection of pills. So I would say this work excellently captured its time. And while generations may come and go, the Combine abides.

Next up: The Long Goodbye, by Raymond Chandler

Amazon links to works related to this post.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey

1984 by George Orwell

Brave New World By Aldous Huxley

The Long Goodbye by Raymond Chandler

Affiliate disclosure: As an Amazon Affiliate, I may earn commissions from qualifying purchases from Amazon.com

Resonates. Thanks!

Gah, I am ready to slit my wrists.....Nice analysis, though!