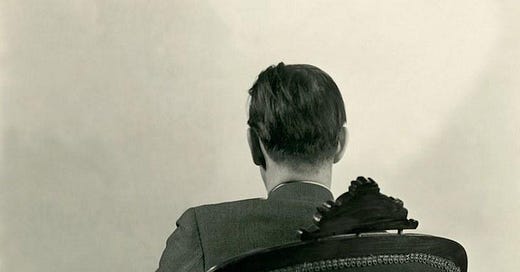

Henry Green published his penultimate novel, Nothing, in 1950. At the age of forty-seven, after just one more novel, Doting (1952), he stopped writing and sank into eccentric reclusion until his death in 1973. He never left his house for the last seven years, and only allowed photographs of himself from the rear.

I don’t recall having ever heard of Henry Green until I came across his name on the Decade Project list, which, by the way, I take with me as a shopping list whenever I go to a used book store. Most people I know haven’t heard of Green either. But he had a profound influence on other writers, whose praise earned him the epithet of “the writer’s writer’s writer.” John Updike says, “my discovery of Henry Green’s novels and of Scott-Moncrieff’s translation of Marcel Proust served as revelations of style, of prose as not the colorless tool of mimesis but as a gaudy agent dynamic in itself…”

Most of my sources describe Green as a modernist, and he has exerted considerable influence over other modernist writers. The conversation flows naturally, replete with pauses, asides, distractions, interruptions, and confusions. The characters misunderstand each other, sidestep direct questions, and conceal more than they reveal, even in their acts of revelation. From start to finish, I thought Nothing extremely funny, but I agree with John Updike that it “do[es] not strike us as purposely comic, but, rather, accidentally so, like reality itself.”

Very little happens in this book, but it happens ever so wittily. Two middle-aged friends, John Pomfret, a widower, and Jane Weatherby, a widow, each have a twenty-year-old child. John’s daughter Mary and Jane’s son Philip decide to get married to each other. After much talk, they break off the engagement and their parents get married instead. But, my goodness, what goes on in that “much talk”!

One could interpret the “Nothing” of the title as a passive-aggressive “nothing”—a one-word response to the challenge, “Exactly what do you mean?” In this exchange between Jane and John about their children’s engagement, Jane both states and illustrates male-female miscommunication as it occurs in Green’s world.

“You are like all men, lawyers every single one. You think there’s no contract until you’ve said yes or had your answer but the chances are you’ve unofficially sworn yourself away forever all unbeknownst quite months before. Which makes it so wicked when you try to back out.”

“Now Jane to what is this referring?”

“Nothing my dear, at all.”

“You were.”

“On my honour. The past’s past...”

Almost the entire book consists of dialogue, but an uninterpreted dialogue. In fact, when the narrator injects himself, he often goes out of his way to amplify the ambiguities. But not evenly, for Green’s women totally outclass the men when it comes to unspoken depths. Of course, a male British writer of the early to mid twentieth century would surely have internalized the biases of his society, even if he sets out to satirize that very society. So Green’s men need no more than surface-level descriptions of their words and actions. We suspect nothing deep about them. But superficial descriptions of the women just lead us deeper into a dark forest of hidden intentions and motives. By the end of the book, because the women seem to have all the life or color, we know less but suspect far more than when we started.

I gather that in Green’s earlier novels he brilliantly captured demotic speech and, in doing so, he adopted the habit of dropping definite articles and verbs. Here, we see a true master of the art. In this conversation between Liz Jennings and Dick Abbot, two supporting characters, he captures an authentic-sounding rhythm of Dick’s speech by selective omissions.

“Have you heard about poor darling John?” she said and giggled. “His doctor’s told him he’s got a touch of this awful diabetes.”

“Good Lord, sorry to learn that.”

She giggled again.

“No one knows. Of course he told me. I’m so very worried for him. Isn’t it merciful they discovered about insulin in time?”

“No danger in diabetes nowadays,” Mr. Abbot agreed. “Rotten thing to catch though.”

Then, after a brief discussion about self-injections Liz continues.

“Does Jane know?”

“The way to give hypodermics? Couldn’t say I’m sure.”

“No no I naturally didn’t mean Jane was a nurse. Has she heard, d’you think?”

“Couldn’t be certain. Not mentioned a word to me.”

To quote Updike again, “At its highest pitch, Green’s writing brings the rectangle of printed page alive like little else in English fiction of this century—a superbly rendered surface above a trembling depth…”

At several points I felt like the narrator hedged every description so as not to convey any meaning at all. He tells us what the characters say but not what they mean or whether they speak truly. Green’s characters don’t speak sincerely, they merely look sincere when they speak. They “agree in a perplexed voice,” or “show signs of indignation,” or “seem pleased.” But the narrator won’t endorse any of those appearances. Even body language conceals realities, for the characters smile “in what might have been a superior manner,” or “appear to listen with care,” or “seem to be lost in thought.” Green even taunts us with descriptions like this: “The tears after a moment streamed down Jane’s face. She might have been able to cry at will or it could be that she dreadfully minded.” But, my goodness, if the narrator can’t tell real from fake tears, how could we?

Philip and Mary plan to become engaged, but Philip grows increasingly worried that they may be related as half-siblings. Their parents knew each other well, and their marriages took place about the same time. But could their friendship have gone further? It would seem like a fairly straightforward matter to just ask their parents, but no one gives straight answers. Instead, now that Green has alerted us to incest as a theme, we begin to look askance at other seemingly innocent relationships.

Green doesn’t always use words to conceal meanings. Sometimes, he uses them to convey information by what they avoid saying. In this passage, John, in an effort to coax some information from Jane, has prepared a lavish meal for her. She starts in on the caviar. He says,

“Well I’ve seen the ring.”

“Oh my dear,” she replied “so have I.”

He considered Mrs. Weatherby very carefully at this response but she was eating her sturgeon’s eggs with a charming concentration that was also the height of graceful greed, her shining mouth and brilliant teeth snapping just precisely enough to show enthusiasm without haste, the great eyes reverently lowered on her plate.

“Did you help Philip choose?”

“Me? Dear no” she answered carefully selecting a piece of toast. “I know better than to interfere ever” she said.

Perhaps John knows no more than before, but perhaps we do. The time it takes us to read about Jane’s bite of caviar could equal the length of John’s careful consideration, or not. In describing the toast, Green omits a crucial comma, leaving us to wonder if she answered carefully or selected the toast carefully. How can charming concentration coexist with graceful greed? Should a shining mouth and snapping teeth make us apprehensive? How should one read this?

For that matter, how should we read the whole book? Elsewhere, Green has described his concept of prose in general as “a gathering web of insinuations.” Indeed, his perfectly clear but frustratingly narrow attention to the merely audible and visible affects us like a photograph of a shadow cast by some menacing offscreen presence. And in the novel’s final scene, John contentedly drifts off to sleep in Jane’s loving arms, while the lives of everyone around them have somehow crumbled. If we didn’t know otherwise, we might think we had just seen a film noir, complete with a femme fatale, disguised as a somewhat giddy comedy of manners.

Next up, A Handful of Dust, an early work by one of Green’s friends, Evelyn Waugh.

Amazon links to works related to this post.

Nothing by Henry Green

Doting by Henry Green

A Handful of Dust by Evelyn Waugh

Affiliate disclosure: As an Amazon Affiliate, I may earn commissions from qualifying purchases from Amazon.com

The crucial comma comment promises a provocative incentive to focus on the idea that Nothing could be Something.