For it is not enough to have a good mind; the main thing is to apply it well. The greatest souls are capable of the greatest vices as well as the greatest virtues; and those who proceed but very slowly can make much greater progress, if they always follow the right path, than those who hurry and stray from it.

—from Discourse on the Method, by René Descartes

I am very pleased to offer to subscribers of the Decade Project a new slow-reading group, Slo-Mo Philosophy, dedicated to major works of philosophy. If you do not want to receive posts related to this group, please go to this link and toggle Slo-Mo Philosophy off. Full participation in the group is limited to paid subscribers. The first book we will read is a classic work by Descartes.

What’s Descartes up to?

In 1641, René Descartes published a Latin essay in six parts, called Meditations on First Philosophy, in which the existence of God and the immortality of the soul are demonstrated. He hoped this work would overcome the growing skepticism of the time about the possibility of knowledge. Unlike other works of non-fiction you may have read, philosophical studies like this one are not all that valuable for their conclusions. What makes them great is that (1) they reveal an intriguing problem in some area previously taken as settled, (2) they propose a novel method for solving the problem, and (3) they attempt to solve it by means of the method. These features are nowhere more apparent than in The Meditations.

Most people are certain that physical bodies (rocks, planets, humans) obviously exist; Descartes shows that if you believe that, you have not thought about things deeply enough. In these meditations, he wants to shake you out of your smug certainty about reality. Then, after some amazing and highly suspect mental contortions, he will reassuringly conclude that bodies actually do exist after all, but it wasn’t as obvious as you thought, was it? Unfortunately, despite his insistence that he has proven his case, the early doubts he raised will probably impress you more than the proofs, and you will almost certainly be less certain than when you started. And that’s how modern philosophy got started.

At the time he wrote, science was not distinct from philosophy, so what Descartes calls “first philosophy,” amounts to what we might call the foundation of physics. While our main interest in him is as a metaphysician, he was also a great mathematician and made contributions to various studies, such as optics, cosmology, music theory, anatomy, and meteorology. Even though many of his contributions were ultimately rejected, he exerted a profound influence on the development of numerous emerging sciences. We still use the Cartesian coordinate system in analytic geometry, for example. But in the Meditations, Descartes applies the method of proof that he developed in his Discourse on the Method (1637) and Rules for the Direction of the Mind (1701, posthumous), to establish what he hoped would be an unshakeable foundation for all future physical sciences. (Calculus, the mathematical tool necessary for doing physics today, would be discovered independently later that century by Newton and Leibniz. Descartes only invented analytic geometry.)

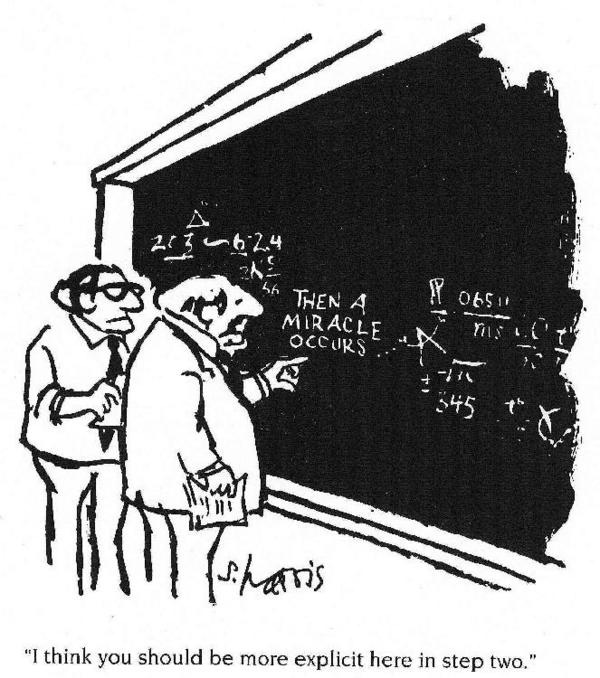

The basic problem with knowledge is that almost everything we know is based on a combination of evidence and reasoning. But if the reasoning is suspect and the evidence is suspect, how confident should be be about the conclusion? Perfect reasoning would only guarantee that our conclusion is no less certain than the evidence. But in a long train of reasoning that requires an intuitive leap here and there we would expect human errors to creep in. Nowadays, we almost always test our conclusions by some mechanical means, like a calculator or a computer. But we owe the very existence of such devices to thinkers like Descartes who analyzed human calculation into tiny steps that even an unthinking machine could replicate without needing an ounce of intuition. The real breakthroughs in this area came much later with the development of modern logic and proof theory, but Descartes saw clearly in the early seventeenth century where we needed to go if we wanted to weed out error from science.

In Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes hopes to use his method for producing error-free knowledge to establish a permanent, unquestionable ground for all future reasoning about the world. While his hopes sound immense, his goal is actually quite meager. He simply wants to prove that physical objects really exist. While that might seem a trivial project, it ultimately proved to be impossible, at least by the approach he took. As you will see, by the third meditation, he had reasoned himself into a corner and found that the only way forward was to prove the existence of a benevolent God. It’s like that famous cartoon where step two of a math proof is, “Then a miracle occurs.”

So, if he failed epically, why read him?

This is a beautiful work of extended reasoning. Descartes wrote it in an engaging, first-person form, and encouraged the reader to participate in the project. He did not write it as a dry report of some results he had reached. He wanted us readers not just to follow along and nod, but to reproduce, within our own minds, the reasoning that leads to his results. He wants us to think, not just have thoughts. And that’s what I hope we will be doing in this read-along. Reading someone’s summary will not turn the steps of reasoning into an experience of reasoning, or, as I might tell my students, “These thoughts will not think themselves.”

A bit of housekeeping

Subscriptions. A paid subscription will give you access to this and all subsequent close readings plus the ability to comment. The Decade Project, my personal struggle to read and reflect on the greatest works of world literature, will continue to be free.

If you do not want to receive either Slo-Mo Philosophy or Decade Project posts in your email, go to this link and opt out.

Editions. For the Medidtations on First Philosophy, you may use any translation or edition you wish. Many are available as PDFs and free of charge. I think it would be fun for us to have different versions. I will be using Volume II of The Philosophical Writings of Descartes, translated by Cottingham, Stoothoff, and Murdoch.

Timing. I will post newsletters on Fridays, to which you may add comments.

Full disclosure, here. In philosophy, I am a generalist, not a specialist. That means I know a little bit about a lot, but not a lot about anything. So I expect to learn along with you as we go.

I suggest we devote one week apiece to each of the six meditations.

Starting today, June 27, get your copy of the Meditations. You are welcome to ask questions, make suggestions, or add comments to this post. (Free)

On Friday, July 4, we will begin reading “First Meditation.” I’ll post some tips on how to get the most out of the first meditation. (Free)

On Friday, July 11, discussion will begin in earnest. I will post my thoughts about “First Meditation: What can be called into doubt.” I’ll say a little bit about what to expect from the upcoming “Second Meditation.” You may add your thoughts or questions as comments, and I hope you will respond to the comments of others. (Paid subscribers only)

On Friday, July 18, following the same format, we’ll discuss “Second Meditation: The nature of the human mind, and how it is better known than the body.” (Paid subscribers only)

On Friday, July 25, we’ll discuss “Third Meditation: The existence of God.” (Paid subscribers only)

On Friday, August 1, we’ll discuss “Fourth Meditation: Truth and falsity.” (Paid subscribers only)

On Friday, August 8, we’ll discuss “Fifth Meditation: The essence of material things, and the existence of God considered a second time.” (Paid subscribers only)

On Friday, August 15, we’ll discuss “Sixth Meditation: The existence of material things, and the real distinction between mind and body.” (Paid subscribers only)

“Do I have to? Will this be on the test?”

No. If you are a paid subscriber, you may participate in the group as actively or passively as you wish. I will make some of my remarks open for all, but the real engagement will come from interacting with other readers.

Obtained the IEP file which is the 1911 ed. of The Philosophical Works of Descartes. Trans by E Haldane. With a bit of tweeking I have a managed a larger font.

Some quaint words here ie perspicuity, essence, accidents... the low hurdles before the jumps get a tad higher..looks interesting so far.

Lovely stuff--bracing (in a low, distorted world)!

Gary Michael Dault