Sir Thomas Browne lived during the greater part of the 17th century, from 1605 to 1682. He published the work I read this week, Hydriotaphia—Urne Burial, in 1658 and followed the next year with a companion piece, The Garden of Cyrus. The latter work did not make it into the Decade List, but an earlier work of his did, Religio Medici, which I plan to read soon.

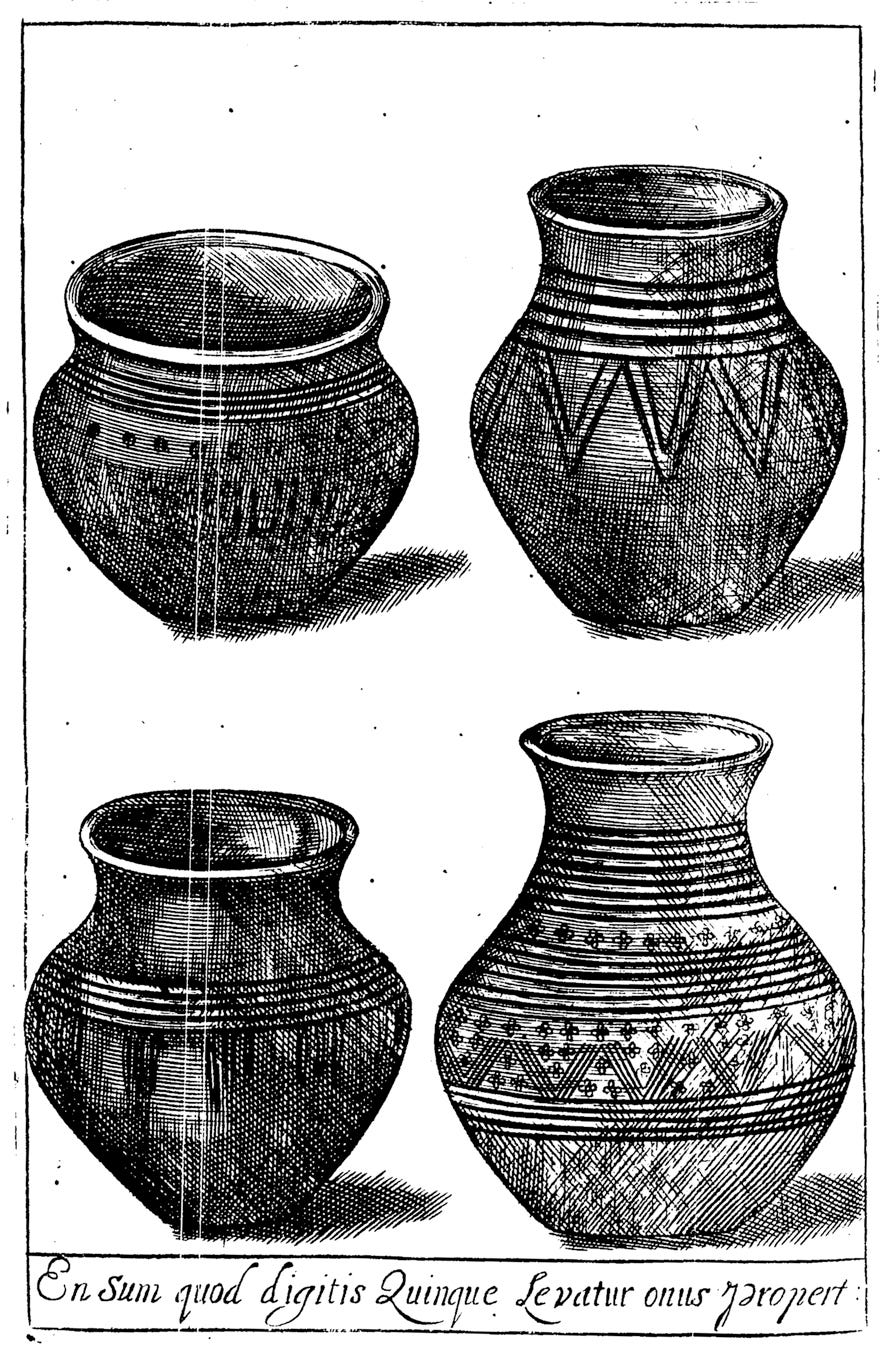

The discovery of several sepulchral urns in a field in Norwich, England, prompted Sir Thomas to write this essay. In it, he describes the urns and their contents—bones, teeth, ashes, as well as combs, small brass handles, and so forth—and explores their archeological significance. I gather this marks the first archeological article ever written. He knew no written information about these urns, no names or epitaphs, and no historical account of them or the bodies they contain. He had only these intriguing finds of the sort that historians must ponder when trying to reconstruct our past. So Browne in the first few chapters leads us through a deductive process as he tries to elicit their secrets. His tentative identification of them as Roman urns later proved wrong. We now know them as Saxon, from a few centuries later than he had thought. To his credit, however, he did not stake his reputation on his conclusion, and he expressed doubts at every step. The lasting worth of this essay depends not on its archeological authority.

Over the course of his exposition, Browne considers the funerary customs of several ages, regions, and religions, drawing comparisons and inferences from them all. He pays particular attention to Egyptian, Greek, and Roman practices, but also considers some from China, India, and the Middle East. He treats every practice with respect, as alien as it may have seemed to his way of thinking. Even on one occasion in which he dismissed something as nonsense—the Greek custom of including coins in tombs to pay Charon’s fee—he also gloated at the wealth of numismatic information it provided.

Sir Thomas, a medical doctor by profession but also a polymath, welcomed the scientific spirit emerging at the time. He took a detailed interest in everything around him, as illustrated by his fascination with these old clay pots found in a nearby field. When the spirit of science gripped him, he asked questions as eagerly as a child, and, also like a child, he seemed open to entertaining any conjecture, no matter how bizarre. He held new ideas up to the light, turned them around, poked and prodded, always asking critical questions of them. His extreme openness to any and every idea strikes me as remarkable. While willing to take all ideas seriously, he remained not overly credulous. His multi-volume Pseudodoxia Epidemica undertakes to investigate and debunk every snatch of folkloric science or popular myth he came across. He scoffed at nothing and questioned everything—except his religion. There, he drew a line he dared not let himself cross.

I found Hydriotaphia, though a mere forty pages long, extremely difficult at first, but so many critics praised its style so highly I kept at it. I now agree with them: English language in Sir Thomas’s hand loses is comfortable famiiarity and becomes both transcendent and idiosyncratic. He has repurposed the language, and almost reinvented it, to serve his vision and precisely express his thought. Apparently the Oxford English Dictionary ranks him high on its list of most frequently cited sources for a word and also on its list of sources responsible for the first evidence of a word. We owe him great thanks for introducing into our language such words as “electricity,” “ferocious,” “prairie,” and “ambidextrous.” Not every neologism of his went on to become as indispensable, however, and that playful, creative wit he exhibits in making language serve his thought sometimes taxes the reader’s own wits trying to follow him.

Sir Thomas does not pander to the reader who expects servile accommodation from authors, but neither does he obscure his meaning by hopelessly personal allusions. He rather gives us in this essay a near perfect meditation sculpted from words so utterly precise as to almost elude us. This problem should sound familiar to many trained professionals: the technical language of any field of study eventually becomes so precise that few outside the field can understand it. Sir Thomas Browne’s mind presents its own field of study with its own technical vocabulary. He found 17th-century English inadequate for his needs, so he matter-of-factly reinvented it.

Even great writers such as Virginia Woolf have expressed some frustration at the difficulty of his prose. In her 1919 essay, “Reading,” she warns us:

Accustomed as we are to strip a whole page of its sentences and crush their meaning out in one grasp, the obstinate resistance which a page of Urne Burial offers at first trips us and blinds us. ‘Though if Adam were made out of an extract of the earth, all parts might challenge a restitution, yet few have returned their bones farre lower than they might receive them’ —We must stop, go back, try out this way and that, and proceed at a foot’s pace. Reading has been made so easy in our days that to go back to these crabbed sentences is like mounting on a solemn and obstinate donkey instead of going up to town by an electric train.

Let’s take the passage Woolf exhibits, and see what we can make of it.

Though if Adam were made out of an extract of the earth, all parts might challenge a restitution, yet few have returned their bones farre lower than they might receive them.

Browne lets the name “Adam” stand for all humans. On the supposition—a false supposition, as Browne believes—that all humans simply and permanently decompose at death, never to rise again, it would make sense that any location on earth would suit for depositing a corpse. It wouldn’t matter how deeply or how shallowly we buried it. But, on the contrary, few people from any age have wanted themselves buried very deep underground. We receive our bones (that is, we come into this world at birth) on the earth’s surface, and we do not dispose of our bones more than a few feet beneath it. The implication Browne lets us draw? At some level, we humans have always anticipated a resurrection, and we don’t want the return of our reconstituted body impeded by many layers of soil.

How do we begin to suspect he means something like this? By reading ahead. The clause Woolf quotes may tempt us to linger, puzzled, without continuing; but we reach the real point only at the end of the paragraph when he calls the practice of shallow burial a “happy contrivance” of earlier generations, by which they unwittingly bequeath their own histories to subsequent generations.

Browne’s technique of holding off the main idea for as long as possible lends gravitas to his rhetorical style. Like a passage of music that takes us to the verge of resolution, he holds us in suspense just a little longer than we think possible, and then a bit longer still. To read one of Browne’s complete thoughts, we must suspend our need for understanding until he deigns to enlighten us. For this reason, I would amend Woolf’s claim that it slows us to a foot’s pace. I think rather we can best enjoy this journey by scampering back and forth over the same passages many times, like a frisky dog that covers miles while progressing only a few meters. While most works of literature run at least 300 pages and this barely takes forty, we can well afford to circumambulate difficult passages many times in widening gyres.

Here. Look at the full paragraph—actually only one sentence:

Though if Adam were made out of an extract of the earth, all parts might challenge a restitution, yet few have returned their bones farre lower than they might receive them; not affecting the graves of Giants, under hilly and heavy coverings, but content with lesse than their owne depth, have wished their bones might lie soft, and the earth be light upon them; Even such as hope to rise again, would not be content with centrall interrment, or so desperately to place their reliques as to lie beyond discovery, and in no way to be seen again; which happy contrivance hath made communication with our forefathers, and left unto our view some parts, which they never beheld themselves.

As with this paragraph, so too with most of his sentences, we must hold our breath until the end before it coalesces into a complete thought. He often uses infinitive clauses or that-clauses as the subjects of sentences which precede their predicates, as for instance in this brief argument favoring cremation.

To be gnaw’d out of our graves, to have our sculs made drinking-bowls, and our bones turned into Pipes, to delight and sport our Enemies, are Tragical abominations, escaped in burning Burials.

Or this expression of surprise.

That Bay-leaves were found green in the Tomb of S. Humbert, after an hundred and fifty years, was looked upon as miraculous.

As sometimes happens when thoughtful people contemplate the crumbling relics of ancient times, Browne’s reflections lead him to thoughts about permanence and impermanence, and the losing battle each person, generation, age, and civilization wages against time. The final chapter, commensurate with its metaphysical ambitions, rises to a pitch of rhetorical grandeur unmatched in my own reading. Other critics from across the centuries have expressed similar reactions. Here, for instance, he broods over the fact that these simple urns have endured intact for so many centuries.

Now since these dead bones have already outlasted the living ones of Methuselah, and in a yard underground, and thin walls of clay, outworn all the strong and specious buildings above it; and quietly rested under the drums and tramplings of three conquests: what prince can promise such diuturnity unto his relicks, or might not gladly say, “Sic ego componi versus in ossa velim” [Thus, when naught is left of me but bones, would I be laid to rest.]? Time, which antiquates antiquities, and hath an art to make dust of all things, hath yet spared these minor monuments.

You might wonder if the effort expended to comprehend this writing yields sufficient reward. Well, yes I think it does. We may not acquire any new facts to smugly tuck away and forget. But we do enter the thoughts of Sir Thomas as he stands at the edge of a precipice—the beginning of a new science. He looks around him in awestruck wonderment. So much lies undiscovered before us, so feeble the instruments at hand, and so misguided the wisdom of the past, we have little to help us but a promiscuous curiosity and a feeble language. Unable to imagine the true vastness of space, the capacity of thought, the depth of the oceans, you and I stand beside Sir Thomas, in the midst of history glancing backward and forward into a darkness stretching in both directions. Standing with him, looking through his eyes, we lose our balance in the presence of Time itself and feel the solidity of the present dissolve around us. Yes, of course the effort has sufficient reward.

While Sir Thomas Browne might not appeal to everyone’s taste, his works have made a profound impression on many men and women of letters. As the Montaigne of English essayists he shaped the style and even the vocabulary of subsequent English prose. He thus holds a significant place in the Western canon and constitutes “required reading” for my project. Required reading or not, Hydriotaphia gave me several hours of great pleasure. The more time I spent with it, the more I loved it.

§ § §

I expect to finish volume 3 of the Mahābhārata in another four days, so I’ll write about it next. If I decide otherwise, I’ll send out a note. Meanwhile, you might want to see what Naomi Kanakia has said about volume 3 in her Substack, Woman of Letters.

A appreciate your reading these reflections of my journey through literature. If you aren’t currently a subscriber, please consider signing up now, for either a paid or a free subscription.

If you know someone who might take an interest in these reflections, please share with them.

Works mentioned in this newsletter

The Mahābhārata, tr. by Bibek Debroy

Hydriotaphia: Urne Burial by Sir Thomas Browne

Collected Essays of Virginia Woolf, volume 3 by Virginia Woolf

I've read it first time, but I think I will read it again soon. There's so much in his stylistics that I enjoy.

From this, I almost could imagine reading this essay myself. :)